Resilience & Joy: Lessons of Da Land

By Gina Myers

January 12, 2022

It all begins with a seed. The seed is both the possibility of future life and the record of what has come before. It acts as a time capsule, telling the stories of people and their resilience—of their lives and the challenges and joys that come along with it.

The act of seedkeeping can connect people to their roots while also preserving crops for future generations. It is a way of passing on cultural information, keeping traditions alive and building community.

Alexis Wiley prepares to fan shelled peas after cleaning. The fanning process removes husks and other materials from the bowl.

Alexis Wiley prepares to fan shelled peas after cleaning. The fanning process removes husks and other materials from the bowl.

The lessons of seedkeeping are ones Alexis Wiley takes to heart. And they are lessons that the environmental science major is now sharing with others.

Wiley developed and led a 12-week cocurricular program titled Lessons of Da Land: Food Sovereignty and Land Justice in Black Philadelphia.

“I wanted to tell the story of Black people’s relationships with food and land, and not just talk about it, but really analyze the changes that have happened globally and historically that have led to the current conditions of food apartheid and land insecurity, as well as the liberation strategies that our ancestors have used throughout our history that would alleviate these issues,” they explain.

This past fall Wiley led 12 students—half Drexel students and half community students—through the course, offering an exploration of the dynamics of food sovereignty and land security in the Black community of Philadelphia by looking at the histories of community agriculture, food apartheid and land tenure.

According to the course description, the "program is designed to be an introduction to ongoing resistance movements and land-based revolutions.”

Access & Collective Knowledge

Throughout the program, learners were exposed to a wide range of sources, including books like The Cooking Gene by Michael W. Twitty, Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land by Leah Penniman and Vibration Cooking: or, The Travel Notes of a Geechee Girl by Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor, as well as podcasts like 1619 and Seeds and Their People, in addition to other materials.

However, the course also moved outside of the classroom and offered a hands-on participatory experience. Working with local community partners, students supplemented their coursework with harvesting, planting, seedkeeping, land rebuilding and food preparation workshops.

It was getting out into the field that was most memorable for MG Gillis, a first-year student studying environmental studies and sustainability who also served as a program assistant for the course.

“In our second class, we went to Land Based Jawns. It was our first group trip to a garden, and it was really nice,” he says. He had entered the farm feeling flustered from classes and other things, but the experience of being in that space had a transformative effect on his mood.

“It was very quiet, which felt eerie because we were on a normal city block. We talked about reverence and different African crops and how the community is living off the crops in that garden,” he says. “You could just feel how the energy in that garden was very comforting.”

Bolden-Newsome gives an interactive tour of the farm space and explains the importance of seedkeeping.

Bolden-Newsome gives an interactive tour of the farm space and explains the importance of seedkeeping.

Community partners included Sankofa Community Farm, an intergenerational, spiritually rooted, African diasporic centered farm in West Philadelphia; Land Based Jawns, an organization rooted in Spirit and ancestral practices that provides education and training to Black women, femme and non-binary people on agriculture, land-based living, safety and carpentry with a focus on self and community healing; and Our Mother’s Kitchen, which runs a camp for Black girls as well as community dinners for adults, both exploring the ways in which Black women authors use food and language as a means of liberation, expression and cultural preservation.

Wiley explains the importance of working with community partners. “Being in the Drexel community, it is easy to think of ourselves as Drexel and forget that we are situated in University City and next to Mantua and on Lenape land. I wanted to make sure that Drexel students got to see more than just our campus,” they say.

They also note why it was important that community learners were also a part of the program. “It’s so valuable and important that people in our communities have space to learn, too, and have access to knowledge that isn’t restricted because of paywalls. We have to make sure we aren’t just keeping information inside of Drexel.”

Additionally, the community members bring a lot of perspectives to the course that might otherwise be lost in a traditional college classroom.

Gillis notes, “It was cool to hear from people who are not Drexel students or affiliated with Drexel. The West Philly community that lives around Drexel is at the backend of the University’s benefits. Drexel students and the University itself has created issues in the community that haven’t been properly addressed, so it’s important to hear from these community members.”

“We also have older people in the class who bring different experiences and perspectives. It creates a more diverse classroom, not just among race, sexuality and age, but also diverse in thought processes and perspectives,” he says.

Wiley adds, “All the people that are involved—students and community learners alike—can share their stories and build knowledge collectively in this space.”

Seeds of Inspiration

Running a 12-week educational program is not a common student experience, but Wiley was uniquely prepared for this.

“No one has ever done anything like this,” explains Steve Dolph, PhD, assistant teaching professor of global studies and modern languages and teaching faculty fellow at the Lindy Center for Civic Engagement. Through his work at the Lindy Center, Dolph helped Wiley develop the program. He also was a student in the course.

“As far as I know, this is the very first Black-owned, student-led, community-based participatory cocurricular course in the history of Drexel. It’s a unique experience, and it has to do with the capacity of this specific individual to lead this kind of program.”

Participants shell crowder peas, a type of black-eyed pea, while listening to seed stories.

Participants shell crowder peas, a type of black-eyed pea, while listening to seed stories.

Though Wiley’s family had moved North from the Carolinas, they always maintained a strong connection to the South and to the land. It is a connection that Wiley has fostered in their own life, through environmental justice work and volunteering and then working at Sankofa Community Farm.

Their relationship to land was deepened through two experiences at Drexel: a study abroad trip to the Bioko Biodiversity Protection Program in Equatorial Guinea and a community-based learning course at Plenitud, a permaculture demonstration farm in Puerto Rico.

At Bioko, Wiley was concerned by what they saw as a lack of access to knowledge across cultures, and at Plentitud, they saw that it was possible to do not only food justice work, but also cultural justice and environmental justice work.

“Those two experiences put in context to me that I get to integrate and bring parts of myself and my culture as a Black person into the environmental work that I want to do,” they explain. “Now what [that integration] looks like is doing food sovereignty and land and security work as it relates to the history of agriculture with Black people and Indigenous people in the Americas.”

Wiley and Dolph worked on developing Lessons of Da Land over the course of a year. The program was made possible through financial and logistical support from the College of Arts and Sciences Goren Fund for Community-Based Learning, the Teaching and Learning Center, the Office of Undergraduate Research and the Lindy Center for Civic Engagement.

Through designing and running the program, Wiley has discovered their passion as an educator.

“This is my first time teaching, though I have tutored before. I was so nervous and stressed out leading up to the first session. Then I was in the middle of teaching, and I looked and everyone had smiles on their faces, the room was really warm and I was looking at my notes, and was like, wow, we really just did that—we really just put all this knowledge together,” they say.

“I felt kind of like a translation tool—like I was able to help them get to these thoughts and conclusions, and it felt amazing. I realized this is what I was meant to do.”

Seeds of Change

For Wiley, some of their favorite moments of the course involved getting to see people experience things in nature for the first time, like when they visited Sankofa and passed around a bitter melon.

“You can see the wonder in people’s eyes as they’re handling and holding these foods and fruits that are a part of their heritage and their stories. It was magical. When we’re handling the seeds and singing and telling stories in the tradition of Black folks, it was just more than I ever imagined this program could be,” they say.

Celeste Sumo, assistant director of civic engagement and operations at the Lindy Center, admires a bitter melon from the field.

Celeste Sumo, assistant director of civic engagement and operations at the Lindy Center, admires a bitter melon from the field.

This experience of joy is every bit a part of the tradition. “Singing, storytelling and expressing your joy not only verbally, but also in embodied ways was a part of the environment I grew up in with my family, my neighborhood and my friends. I didn't really understand or contextualize the significance of how essential it is to Black culture until I started working at Sankofa, where we're very intentional about honoring Black culture,” explains Wiley.

“So when I started developing this course and reading our history and the practices of liberation in that, I learned we're not just singing to sing, or dancing to dance, or talking to talk. We do these things because they're freeing for us. They're part of our expression.”

Wiley knew that this had to be part of the course. “I can't separate this practice from the storytelling. They have to go together because that's always how they have been.”

Dolph was particularly moved by this way of learning. “The way we approached material isn’t just with our academic analytical side. There’s singing, prayer, touching the land, listening to the space around us and interacting with foods. It’s been really enlightening to just sit with those ways of learning about food and culture,” he explains.

“It was really nice to be able to participate in the act of preparing seeds for keeping and to know that those seeds would become a part of a much larger network of food and knowledge exchange,” Dolph says.

“That is itself a recovery of ancestral practice of food saving and knowledge saving that preserves the lives and lifeways of a people who our culture tried to exterminate. So it felt profound to connect to and be invited into that practice of food keeping and cultural archiving.”

The course helped Dolph see the trajectory from Reconstruction and the transatlantic slave trade to the food and resource insecurity that exists in Black communities today, as well as the proliferation of African food throughout the Americas.

“The course has allowed me to see the exclusion of and devaluation of Black life in a much more profound way that connects to a food system that I participate in. What do we do in the face of such profound injustice and such profound structural violence against Black life?” Dolph asks.

“This course creates the conditions for someone like me, an outsider and an academic, to be able to see connections and pathways to action and change.”

That is what Wiley hoped people would take away from the course. “I want people to understand why collective knowledge building is important and imperative for social change. When we do this work together and when we understand each other’s perspectives and stories, it creates a type of understanding that can be translated into action,” they say.

“For the Black folks that were in the cohort, I wanted them to leave with a sense of themselves—of knowing their history and knowing their stories. To know your ancestors is to know yourself, and so I wanted to make sure they left understanding their lives a little better, understanding the community a little better and feeling more situated and grounded in their experience.”

This was the experience for Gillis, who grew up in Philadelphia and hadn’t thought much about food sovereignty until this class. “I’ve learned about the intersection between the environment and social justice issues more intimately through speaking with people about their experiences, but also through considering my own experiences and looking at my family history,” he says.

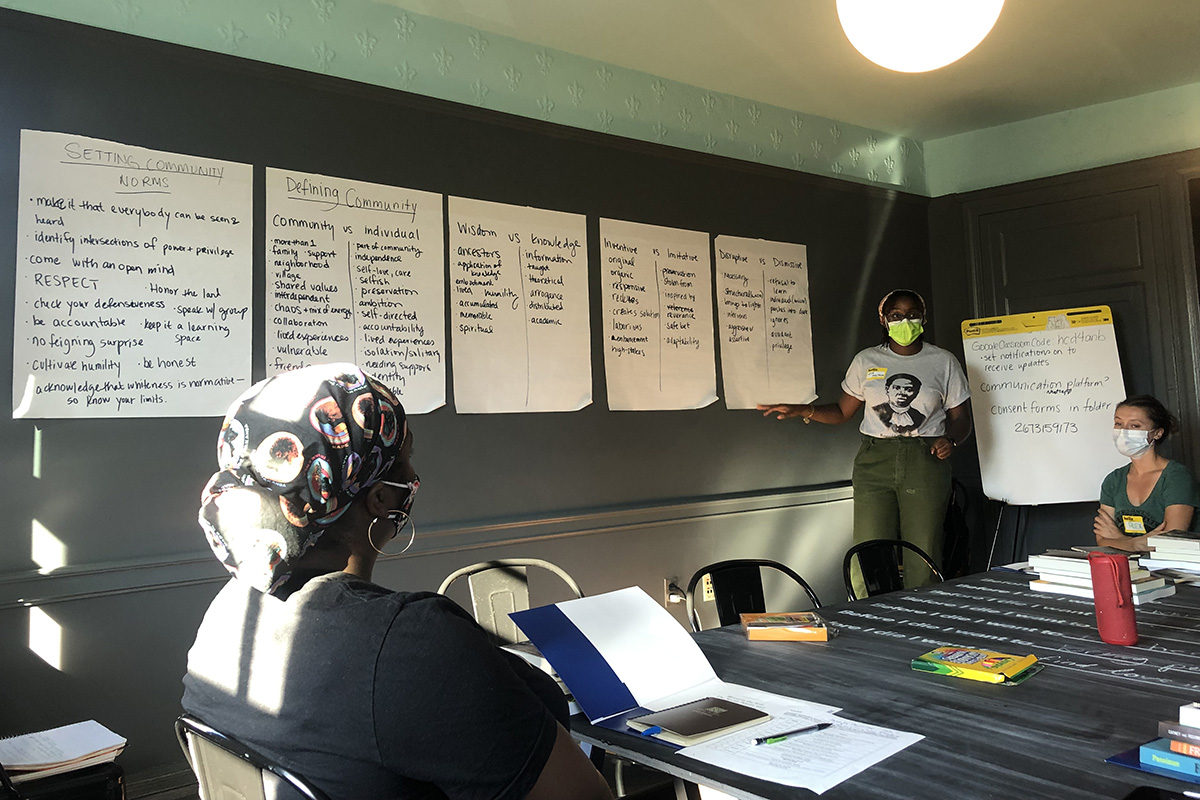

Wiley reviews the first lessons of the program.

Wiley reviews the first lessons of the program.

“It has made me more passionate about social justice and the environment, and it has helped me be more observant and grow as a person. It has caused me to really think about what I am learning in school and how I am applying it to my life,” he adds.

For those in the class who are not Black, Wiley hopes they left the course with an “understanding of what Black people are going through, and that they use that understanding and their connection to this experience to incite action and change in order to create more solidarity with our issues.”

What’s Next

After graduation this spring, Wiley plans to take a gap year to continue to work as a farmer and educator. They are trying to imagine what Lessons of Da Land will look like outside of Drexel and solely as a community program.

They are also at heart a scientist and a researcher, so they plan to go to graduate school.

“I want to get my PhD in something related to agroecology or Black geographies in order to understand how slavery has impacted biodiversity and ecological relationships in the Americas, but with an equal focus on the natural ecology that's happening with plants and animals, and the human ecology. What are the relationships between people and the relationships from people to the land? I want to make sure that, in that research, I tell a comprehensive story of what happened in America so we can better understand what's happening now.”

They also want to be a heritage farmer in a cooperative that values learning and sharing resources to build resilience and invest in the community.

“No matter what I do, from grad school to farming, teaching is always going to be a part of it,” says Wiley. “I think it has to—it’s essential to the work of trying to abolish oppressive food systems and environmental injustice systems.”