Let’s Talk About Climate Anxiety

By Brigette Brown

June 03, 2022

Lately, there has been a lot of talk all over the world about the birds and the bees — that is, how they are impacted by the environmentally devastating effects of climate change and how humans play a role in this process. Many of us want to know how we can voice those scary feelings about the health of our planet and then transform them into positive action. While it is an important and timely topic to discuss, sometimes having this talk can be a challenge, especially with children.

Tell us about yourselves.

Lena Champlin: I am an environmental scientist and artist, currently a fourth-year doctoral student in the BEES department at Drexel University and a research associate at the Academy of Natural Sciences. My research focuses on coastal water quality changes over space and time and using environmental data to measure changes in coastal ecosystems. I am interested in using artwork in outreach to teach environmental science topics to students and families.

Jeremy Wortzel: I am a fifth-year MD/MPH student at the University of Pennsylvania, pursuing a career in child and adolescent psychiatry at Brigham and Women’s Hospital next year. With a passion for environmental and social justice, I have focused my clinical work and research at the intersection of toxic environmental stress, green space, climate change, pediatric development and mental health.

What’s the story behind your book?

JW: Some of the inspiration from this project came from a conversation Lena and I had together, after Lena had an interaction during an outreach event at the Academy of Natural Sciences where, as she was about to describe climate change to a young girl, the girl’s caregiver quickly pulled her away and said, “We don’t talk about climate change yet.” This was an interaction I was familiar with when it came to conversations about death, divorce and “the birds and the bees.” Therefore, it became evident that just as we provide resources for families to delicately navigate those other nuanced conversations, similar materials would be needed to approach climate change.

LC: Jeremy and I were excited to work on a collaborative project together. Coming from different fields, environmental science for me and child psychiatry for Jeremy, we have a lot of conversations about how to teach climate change in a way that opens it up to talk about feelings and how to best inspire action. I think that fear of climate change makes it challenging to bring up this topic so having a resource to help start these conversations is important.

So, what exactly is climate anxiety?

JW: Climate anxiety, or climate-related distress, is a term used to describe the emotions that people feel when thinking about their climate future. There is also a growing body of evidence to suggest that climate anxiety in young people is quite pervasive. In a recent Lancet article, published last year, a survey was given to 10,000 young people (ages 16–25 years old) and asked them about their feelings regarding climate change. Over half were either worried or extremely concerned about their future and 40% were even hesitant to have children given the impending changes to our world due to climate change. The term “climate anxiety” has recently been incorporated into psychiatric literature, and the mental health field as a whole has begun taking this topic seriously. The American Psychiatric Association and the Group the Advancement of Psychiatry now both have committees dedicated to thinking about how climate change impacts mental health.

LC: From an environmental science angle, I have observed feelings of fear about climate change in my colleagues, undergraduate students that I teach, and families who I have talked to at outreach events. In all the earth sciences classes that I have taken and helped teach, we do not talk about climate anxiety. I believe that climate anxiety is especially impacting children, but also their caregivers, and that this anxiety can lead adults to avoid or not want to start crucial conversations about climate change.

Why should we have these crucial climate talks, especially with younger people?

LC: Like other challenges topics such as death and divorce, starting conversations at a young age builds a foundation of understanding and presents an opportunity for continued discussion. Climate change is a similarly challenging topic that we may not be comfortable talking about even as adults, however talking about climate change is critical to inspire action in ourselves and others. Creating stronger relationships surrounding climate action between adults and children is essential in taking action against climate change.

JW: The way young people are introduced to the topic of climate change is vital to how they approach this material later in life. The traditional narrative of climate change teaching is “my older generation messed up and now you the younger generation needs to fix it.” With this trope, we see many people overwhelmed by climate change as the burden of fixing this problem is placed entirely on them. This can make individuals run away from this material. However, if we change this narrative to one that is empowering and welcoming, we can engage young people in this conversation.

How do we change the narrative and make this conversation engaging for everyone?

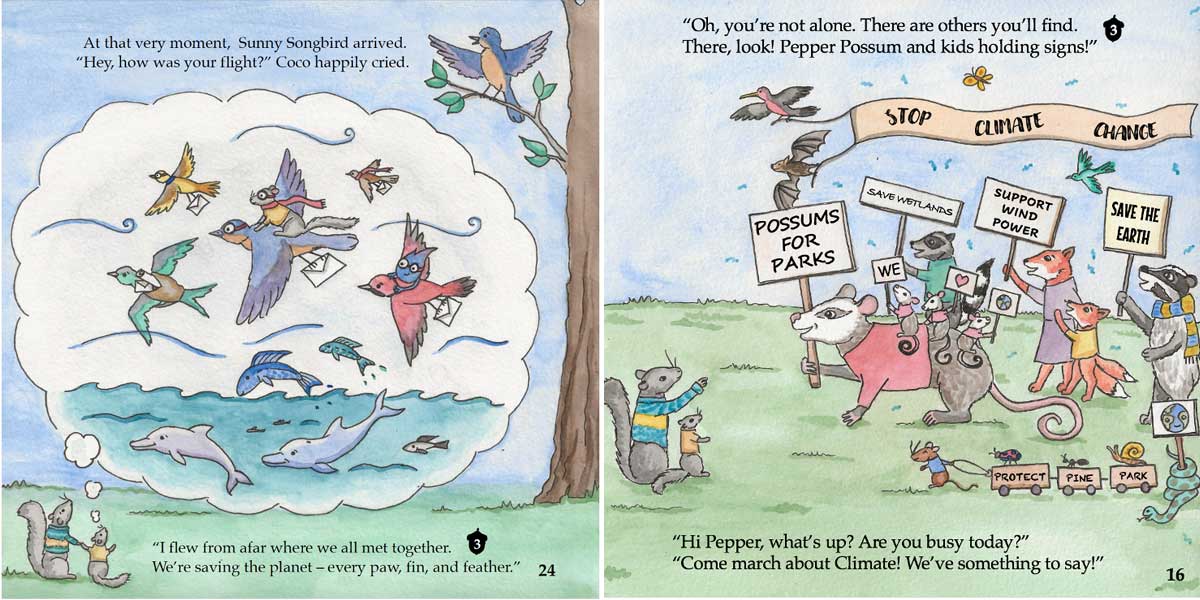

LC: In our book we present a six-point framework for starting a conversation about climate change. This includes first starting with an introduction of the topic by finding out what the child already knows about climate change. Then, explaining the science in a simple, approachable way using metaphors. Next, providing hope, but not sugar coating the problem. Also, discussing solutions and ways to take action. Inviting future conversations and more discussion of emotions. Finally, inspiring care for nature and environmental wonder.

JW: Age is a really important factor when considering the nature of this conversation. For younger individuals (those younger than 6 or so) it’s important to introduce climate change gradually. It’s okay to start by creating a sense of wonder in the natural world and encouraging young people to spend time outside. In this way you can save more of the science of climate change and its consequences for when they may have a more concrete operational stage of development and can contextualize those long-term ramifications. When considering discussions on this topic with adult peers and friends or even those that deny the impact of climate change or its anthropocentric origins, it’s important to recognize the anxiety that may be under the surface and emphasize the thriving community of politicians, activists and scientists working to address the concerns and how they can get involved.

LC: It can also be helpful to talk about community and collective effort against climate change, rather than focusing on just individual actions. Local examples of climate change impact on specific ecosystems and animals can be easier for people to relate to and recognize. For example, telling the story of the specific changes of oyster populations in a nearby bay may be more relatable than carbon dioxide levels in the global atmosphere. Stories and metaphors that support more connection between people and the environment (rather than increasing fear of the environment) are important. For example, when talking about ocean acidification, rather than making the ocean scarier by describing the harm that an “acid ocean” can cause to people and animals, we can start by describing the essential role the ocean plays as the circulatory system of the Earth.

We’ve learned about our environment, and we’ve started the conversation. What else can we do to recognize and address climate anxiety?

LC: Learning about climate anxiety is an important first step. When we recognize that it is occurring, we can change our approach to teaching and learning about climate change to include time for talking about our feelings surrounding it. Although climate change is huge and daunting, joining efforts to take action against it can help reduce climate anxiety. Being involved will create important opportunities to talk about problems, make connections and reduce overwhelming feelings. Getting involved in climate change action includes supporting local politics, writing to politicians to show your support of environmental action, joining protests and activism, and supporting climate science research by scientists.

JW: The points Lena brings up are excellent and getting involved is the first step! However, if folks are really struggling with their anxiety regarding climate change, consider seeking out a climate aware therapist. These are therapists that incorporate these discussions into their practice and can provide some guidance. The Climate Psychology Alliance and Climate Psychiatry Alliance are two organizations that can help connect you with additional support if needed.