Dispassionate Observation in Art and Medicine at West Reading

March 30, 2022

By G.K. Schatzman

First-year medical students at the College of Medicine at Tower Health honed their observational skills this February during the “Dispassionate Observation in Art and Medicine” event with neurobiology and anatomy faculty member Kelly Brenan, MD.

“For me and a lot of medical students, we see art and science as the antithesis of each other,” said first-year Gopal Topiwala, who attended. “But I think in reality, they’re sort of going after kind of the same concept. Like with pattern recognition: When you analyze art, you’re analyzing patterns. In science, as a pathologist, you might be looking at slides to analyze patterns and find what’s going on. So I thought it was interesting to connect those two things.”

Paul Scalzo, a first-year medical student who participated in the event, was also intrigued by the title. “I’ve always thought medicine to be a passionate profession, and I’d never heard of ‘dispassionate observation’ in relation to medicine.”

The session began with a group of around 20 medical students – members of the first Drexel medical cohort at the new West Reading Campus – gathering to discuss the concept of dispassionate observation, which involves learning to put off biases and premature assumptions by making low-inference observations with what Brenan calls the “profound diagnostic tool” of one’s own senses.

“Historically, visual observation was a key tenet of physical examinations before we had all these sophisticated diagnostic tools. There was great care in visual observation. Now, it’s so much easier to just go get a CT scan,” Brenan explained. “The premise of this session is that there’s so much power in the visual inspection of a patient. It’s one of the few diagnostic tools that’s free. It’s available at every level of care. It’s available at all locations. And unlike a laboratory or radiology study, there is zero risk for the patient.”

After the initial discussion, students practiced those observation skills with donor body patients, the value of which Brenan knows well from her own work with post-mortem examinations. “Visual inspection in the post-mortem setting is a unique experience because many of the emotional barriers that exist for a caregiver with live patients are not present in this setting,” she said. “I challenged students to examine the donor organs and bodies, in the simplest of terms: color, shape, contrast and quantitative assessment, such as measurement with a scale or ruler.”

Learning to observe fully and without discomfort remains critical to diagnoses and patient outcomes. As Brenan explained, “The presentation was an expansion of a brilliant paper written by prominent Stanford physicians (Abraham Verghese et al.) who explored how many misdiagnoses result from a failure to fully visually examine the patient.”

Many of the misdiagnoses mentioned in the paper resulted from the failure to fully examine areas that can be emotionally uncomfortable for both parties, like the perineum. “That area doesn't know it's an uncomfortable area to examine,” Brenan said. “It sees itself as just as capable of creating diseases as any other parts.”

For students like Abigail Murtha, a first-year medical student in the Medical Humanities program for whom art has long been a central part of life, the session was also an opportunity to explore ways to integrate their artistic side into their development as physicians. “I was really interested to hear how Dr. Brenan and other physicians had integrated the humanities as a part of their lifestyle,” Murtha said. “I had always kept those two things separate as a part of myself.”

Murtha enjoys painting, when she can find the time. “I’m looking at all the unfinished canvases and paint palettes that are sitting around,” she said over the phone. “With any hobby, it can be difficult to continue that in medical school.” But she isn’t the only med student from her cohort with an arts background. Murtha counts herself lucky to be one among many creative colleagues, some of whom have hosted events throughout the year. She is even considering starting an arts club to help students develop that side of themselves in community during the busy stages of medical school.

“One of the ways that I’ve tried to maintain my life as an artist has been by joining the Medical Humanities program,” Murtha said. “I think that Dr. Brenan and other professors have it right, that you can really marry those two skills.”

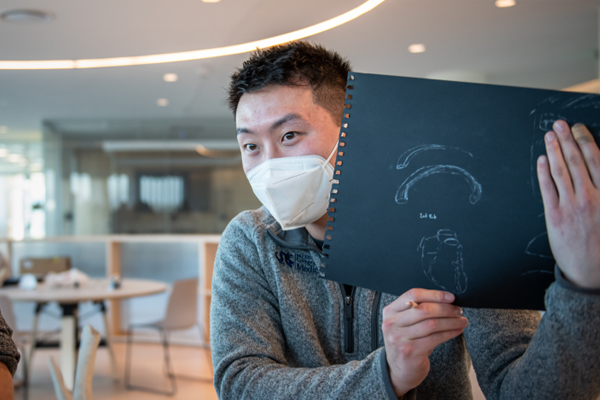

That’s what drew Scalzo to participate in the session, too. “Our class has artists, dancers, musicians. I’m not one of those,” he said. “I wanted to take a look at something I’m not particularly strong in and use it to learn more about medicine.”

Topiwala added, “Dr. Brenan is pretty uniquely qualified to teach us this. She’s not only a medical doctor, but she also went to art school and is currently involved in the arts. Her background as a pathologist makes it even more interesting.”

Brenan herself praised this cohort’s artistic talent. “The class is extremely talented. The university itself feels very intellectually and artistically robust,” she said. “This program is really tapping into a lot of the talent within the group and channeling that to their education and now also to the patients they serve.”

For Murtha, the session was about learning to observe with detail in order to build the bigger picture, rather than working the other way around. “As medical students, we often overcomplicate things, unfortunately – looking for the bigger picture, looking to see if something is diseased, rather than asking ‘What is the texture of this thing? What is the color?’” she said.

Scalzo saw it as an exercise in learning to let the patient’s body teach you. “It was kind of the opposite of what my idea of it was. The dispassionate observation was about removing your biases and stereotypes of the situation,” he said. “It actually aligned with a lot of my own ideas and passions.”

Topiwala appreciated the chance to become both more procedural and more creative in his diagnoses; since diseases don’t present the same way every time, putting aside assumptions while you gather visual observational data feels important to him. “I think dispassionate observation allows for a broader differential diagnosis,” he said. “It allows us to be more creative, which is not really a word you hear a lot in medicine, but I think it’s a good skill to have.”

Students at the West Reading Campus can look forward to more events in this series. An upcoming session will spotlight a student who is a former carpenter, and plans are underway to create mosaics from upcycled pottery at a community pediatrics clinic.

Dr. Brenan acknowledges the tremendous support of Daniel V. Schidlow, MD, former dean of the College of Medicine, who now serves as director of West Reading’s Bioethics and Professional Formation course, Karen Restifo, MD, JD, regional vice dean of the College of Medicine at Tower Health, and academic coordinator Andrea Bensusan. She expresses gratitude to the team at the gross anatomy lab where part of the event was hosted, and to the donors to the Human Gift Registry on whose bodies the students practiced observation.

Brenan also gave a rousing shout-out to the first-year cohort, the first group of medical students at the brand-new campus. “They will always be the first class, and there is an amazing energy with these students that is so much more than medical school,” Brenan said. “It’s like nothing I ever thought could happen. It’s a Zeitgeist of enthusiasm and a desire to learn.”