Field Notes

The Unsung, Unpublished Adventures of Drexel Researchers in the Field

January 16, 2018

Illustrations by Natalie Vaughn ’18

The Tale of the Mysterious Manuscripts

Alden Young, PhD

Historian

Destination: Cairo, Egypt

Research Site: Bookshop of Mustafa Sadiq

Research Subject: Sudanese History

Sometimes the best gifts arrive in the mail. In the spring of 2015, just as I was attempting to revise my dissertation into a book — “Transforming Sudan: Decolonization, Economic Development and State Formation” — three Arabic manuscripts arrived in the mail. They were perfect for the project. Each one of the manuscripts was about a series of lectures on the Sudanese economy that was given in Cairo from the late 1930s to the late 1950s. A fellow researcher had posted them in the mail — but where had they originally come from?

Archival research in the Middle East and much of Africa can be immensely frustrating. I was lucky to have conducted much of the research for my dissertation in Sudan where, unlike in Egypt or Syria, the state archives are relatively open. However, I had hit a snag that will be all too familiar to researchers working in postcolonial countries. While the National Records Office was well equipped, I soon discovered that the list of books I had brought with me from the U.S. — the references I needed to complete my work — was useless. Years of budget cuts and devaluations had left the library completely underfunded, and slowly, the collections had been sold off one by one.

When I received the mysterious manuscripts, it was a clue that the texts I needed were out there somewhere. So, armed with half-remembered instructions from my fellow researcher, I traveled to Cairo in November of 2015. Conflict and a lack of funding have transformed the used booksellers of Cairo and Damascus into the literary storehouses of the Arab world, but unlike formal archives, the old bookstores can only be found through word of mouth.

With the guidance of my colleague, I made my way to the Sultan Mahmud’s Takiyya (a large complex in old Cairo) and eventually, to the basement bookshop of Mustafa Sadiq. There, and in the dozens of shops like his spread across the city, one can find 19th-century books on Egyptian agriculture and geography, George Orwell’s “1984” and even medieval books of magic. Mustafa was at first skeptical, believing that I was just another curious person off the street, but I passed his test when I gave him the name of my colleague. He opened his shop to me and displayed his collection, one of the many that provide the archives for our histories of the Arab World — exactly what I needed to finish my book.

Wild Dogs in the City

Robert Kane, PhD

Criminologist

Location: New York City

Research Subject: Police Misconduct

Follow-Up Protocol: Rabies Vaccinations

My day as a field researcher began like most others at that time: I caught the 4/5 train at 86th and Lexington for my morning commute to 1 Police Plaza in Lower Manhattan. As I made my way above ground, I felt my cell phone vibrate. The caller was John, a veteran detective I employed on his days off to help me collect data for my historical study of police misconduct in the NYPD.

“Rob, we have a problem,” John said. “We’re missing a bunch of records from the 1980s that we need to complete the files.” He speculated they’d been moved to a warehouse on the outer edges of Brooklyn.

“How do we get them?” I asked.

“We need to take a ride,” he said.

Ten minutes later, I was cruising with John and Todd (another detective who worked for me) across the Brooklyn Bridge in an unmarked police car. When we finally pulled to the curb about 40 minutes later, we were in Sheepshead Bay.

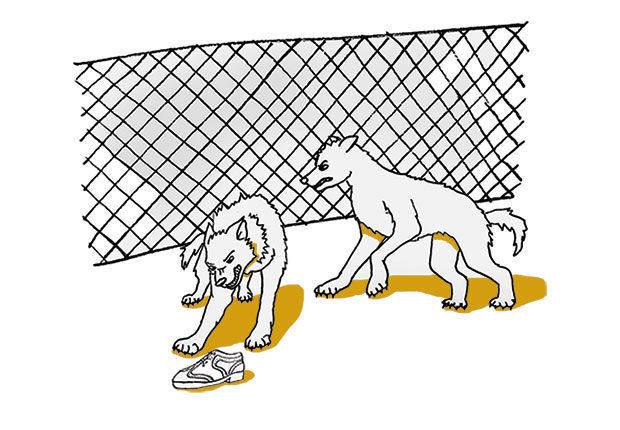

The area was vaguely industrial, with a huge vacant lot fenced in by chain link that was at least 6 feet high. As we locked up the car, I saw John and Todd both check their weapons, which immediately made the hair on my neck stand up.

“Gangs out here?” I asked.

“Wild dogs,” Todd said casually.

Not wanting to appear the rube, I didn’t ask for clarification. I thought maybe there was a gang that my research had missed called the Wild Dogs.

Next thing I knew, Todd and John had scaled the chain link fence and were looking at me from the other side. When I protested, one of them said, “It would have taken too long to get permission.”

Shaking my head, I climbed the fence and quietly cursed the jacket and tie I was wearing.

After 10 minutes of traversing the weeded, crumbling blacktop surface, we came to the warehouse. Or rather, the dilapidated Quonset hut with broken windows and no lock on the front door. Our experience inside that hut, rummaging through water-damaged boxes and fighting off rats the size of raccoons, is its own story. Suffice it to say, after about two hours, the three of us were hauling a box of old personnel files back to the car when I heard the barking.

“Here they come!” one of the detectives shouted.

“Run!” the other yelled.

In a flash, we were galloping toward the fence, though I didn’t know why. John was leading while Todd and I tried to keep pace, straddling the large, heavy box. The barking turned to snarling, and over my shoulder I saw a pack of dogs closing in on us.

“I thought you were talking about a gang!” I screamed at John between heavy gasps of air.

John scaled the fence in a single stride, but Todd and I were too weighed down to accomplish the same feat. We hurled that nasty box of personnel files over the fence while John drew his pistol and yelled at us to hurry up. As Todd tumbled to safety and I threw one leg over the fence, one of the dogs leaped after me and clamped down on the heel of my shoe, ripping it from my foot and sending a searing pain through my entire leg. I made it over and fell to the sidewalk just as the remaining dogs — five of them — crashed into the fence, all head and fangs, using every bit of strength to get at us.

It wasn’t until the last one of them finally trotted off — the one with my shoe clenched in its teeth —Todd and John began laughing. Partly at the situation, but mostly at me.

“Welcome to the NYPD, Professor!” they exclaimed.

Fourteen rabies shots and one new pair of shoes later (a gift from Todd and John), I was just beginning to see the humor in what had happened.

Monkey Business

Debjani Bhattacharyya, PhD

Historian

Destination: Delhi, India

Research Subject: British Raj

File Request: Pension Scheme for Gray Langurs, 1942

As a historian focused on the British Raj in India, I spend many hours in dusty archives poring over old documents, from intriguing tales of treachery to mundane budgetary debates. I have spent countless hours in such dusty rooms across continents from London to Delhi. On one such trip, a file popped up on the records: “Pension Scheme for Gray Langurs, 1942.”

Langurs, for those who have not visited South Asia, are a variety of monkey found across Pakistan, India, Nepal and Bangladesh.

Well, this was curious, I thought. So, I ordered the file.

It seems then that, as the British colonials were tearing down the forests to build New Delhi, they depleted the habitat of the local monkeys. Some of these displaced monkeys found a new home on the campus of Delhi University. Young students, absent-minded professors and monkeys tried living and learning together — but not for long.

Soon it turned into pure monkey business and the education board took matters into their own hands. The monkeys had to be chased away — and who better suited for the job than their fellow primates, the great gray langurs?

Delhi University employed langurs to chase away the other monkeys, and when the first batch of these professional langurs in the service of the British Empire was about to retire, a pension scheme was devised. After all, they had dutifully served the world’s largest empire.

As I turned the last page of this curious entry from 1942, I heard a commotion coming toward the reading room of the National Archives of Delhi. People were running out, and I picked up my laptop and followed the crowd. Soon, I saw I was being chased out of the archive by none other than two little monkeys! And there I was, witnessing history repeating itself — rather farcically!

Your Space or Mine?

Jason Orne, PhD

Sociologist

Location: Chicago

Observation Site: Jackhammer Bar

Research Subject: Urban Sociology and Sexuality

It’s so dark when you reach the basement at the bottom of the stairs at Jackhammer, a gay bar on Chicago’s North Side, that it takes a few minutes for your eyes to adjust. When I was doing fieldwork on urban sociology and sexuality in Chicago’s gay bars and clubs, I had to follow the rules just like other patrons. On reaching the bottom of the stairs, I would take off my shirt and don a leather harness. Sometimes the others, and therefore me, had on even less.

The scene across town at Cocktail, another gay bar in Chicago’s Boystown neighborhood, was quite different. I once sat around a high-top table of straight women there for a bachelorette party. The straight male stripper came over to our table, rubbing himself along the bride-to-be’s body and leaning his beefy arm over her shoulder as the women giggled and slipped a few dollars in his underwear. Some gay bar, right?

As gay people become more accepted in American society, the bars and clubs that we go to change. Straight people come in looking for a good time and change the dynamics of the space. Gay men flee out. As an alternative culture that has different views of sex and unique communities built around sexual spaces, gay neighborhoods are losing some of their sexual vibe as straight people come into them.

At the bottom of the stairs at Jackhammer though, in the back hallway, past the freezer and the boiler, I would see, in the flickering lights, gay men connecting in the dark. Using sex as a way to have fun, but also to bridge boundaries and form communities. Once, in the corner under one of the dripping water pipes, I also saw a straight couple. The woman, topless, her long brunette hair falling around her shoulders, was swinging in time to the thumping music overhead.

Perhaps, I thought, we can even have these spaces in common.

Let Sleeping Beasts Lie

Loÿc Vanderkluysen, PhD

Volcanologist

Location: Yellowstone

Permit Authorized By: U.S. Park Service

Research Subject: Volcanic Gas Emissions

Yellowstone is a place that has long captured the public’s imagination for its spectacular landscapes, pristine ecosystems, wildlife, geysers and other geothermal features. For a volcanologist like myself,

the oldest national park in the U.S. offers countless opportunities for research.

In September 2016, our team traveled to Yellowstone to conduct a survey of volcanic gas emissions under a research permit from the National Park Service. Over the course of our field campaign, we rapidly grew accustomed to encounters with wildlife on the roads, particularly elks and bison. Indeed, we spent hours blocked in what park staff affectionately call “bison jams” while attempting to reach our field sites.

On the last day of our campaign, we set out to study gas released by Lone Star Geyser, only to discover a large bison already there. It was a cold day, and bison often seek the warmth and comfort of such geothermal areas at those times. Luckily, the animal was resting in the grass at a safe distance, and we were able to set up our instruments and start collecting data.

As the morning turned to afternoon, however, the beast started awakened and developed a growing sense of curiosity for our equipment, slowly creeping toward us. We backed away, abandoning our tools and field site to the animal’s good graces.

Fortunately, the bison was soon distracted by tourists and decided to leave our infrared spectrometer unscathed. It still amazes me, though, that I have grown more fearful of the wildlife that inhabits volcanoes than of the volcanoes themselves.

Up Stream Without a Compass

Mary Katherine Gonder, PhD

Biologist

Destination: Cameroon, Africa

Terrain: Tropical Forest

Research Subject: Chimpanzees

During my PhD dissertation research, I spent a lot of time in Cameroon in Central Africa. On my first field excursion, I went out with my project assistant and several other researchers to study chimpanzee nests. We set camp about six hours into the forest and headed out on the trail with our assigned eco-guard. He marked our path using a hip chain and spool of thread, which he let out behind us over the course of several hours. When the sun started to set, we began to make our way back following the trail of thread — only to find about 100 meters in that the thread was no longer attached to anything.

Lost in the bush, we decided we could make our way back to camp if we could find a stream. At the time, I didn’t appreciate how much streams wind in tropical forests, and as it turned out, we couldn’t use this as a navigational method. By sheer luck, we managed to find our way back the next morning, and the eco-guard convinced us that the broken thread had been a freak accident. Foolishly, I believed him.

We went out again that day only to have the exact same thing happen. I knew we couldn’t follow the streams, so we went to the highest point to get a GPS reading — to no avail. Now completely lost, we walked for three days without food, water or camping supplies.

Fortunately, one of the researchers was a smoker, so when we stumbled upon a flip flop in the forest, we were able to cut off little pieces to start a fire each night. We cooked up tiny, 3-inch fish that we killed with rocks, and slept on leaf beds like gorillas.

By the end of the third day, I was so exhausted I didn’t think I’d be able to walk in the morning. As I lay on the ground, a group of driver ants (the ones with giant claws) got into my clothes, and I had no choice but to jump in a nearby stream. I quickly pulled off my shirt, not realizing my compass was in it — and there went our last navigational tool, downstream with the ants.

At about 2 a.m., I saw the bright light of a hunter’s headlamp in the forest. I jumped up and yelled for help, fully aware that a white woman in the forest was a pretty unusual sight in Cameroon. The hunter came to our rescue and agreed to take us back to his village — another 12 hours away by foot. At this point, we were starving. The villagers fed us cocoa yams when we arrived, and we gratefully indulged. They told us we’d have to cross a large river to get back to camp, but fortunately, they had inner tubes and they graciously pushed us across the river as we sat feasting on yams.

On the other side of the river was a cocoa and coffee bean farm. Once or twice a month, a truck picked up their shipments, and miraculously, it was there when we arrived. We hitched a ride back to the Wildlife Conservation Society headquarters, holding on to giant sacks of beans in the back of the truck.

It was Thanksgiving Day when we finally arrived at WCS. I called my mom to wish her a happy holiday, and didn’t tell her about my near-death experience for another 15 years.

I learned a lot about myself in those six days. I realized how dedicated I was to my fieldwork, which is probably why I still do it today. But most importantly, I learned that, even in the most difficult moments, when there seems to be no way past a particular hurdle, if I can find a way to work through the problem calmly, there’s almost always a solution.