Indoor Dining and COVID-19: Implications for Reopening in 30 U.S. Cities

This brief is part of a partnership between the Drexel Urban Health Collaborative and the Big Cities Health Coalition to support and contribute to the Coalition's vision of healthy, more equitable cities through big city innovation and leadership. This is the first in a series of briefs linking data and policy at the local level. While this brief reports on policies in the 30 member cities of BCHC, it does not reflect the position of the Coalition or its membership.

Download the Brief

Background and Purpose

After several months of strictly limiting restaurants to delivery, take-out, and curb-side pickup services, cities across the U.S. have begun to allow food establishments to offer on-site dining.i

Without federal regulations, decisions on reopening are left to municipal and state governments. As a result, the timing of reopening has varied significantly across the country. Cities in Texas opened indoor dining facilities on May 1st while cities like Chicago, Oakland, and Denver waited until late June and early July.ii There are some cities where indoor dining has yet to reopen. In the cities that allow indoor dining, both the U.S. Food & Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention established guiding principles for reopening to encourage restaurants and bars to operate safely.1 The guiding principles, which are intended to supplement any state or local regulations, fall into the following four categories:

Social Distancing

- Limit seating capacity

- Change dining area layout to keep parties at least 6 fix apart

- Increase circulation of outdoor air by opening windows and prioritizing outdoor seating

Food Safety/Hygiene

- Avoid offering self-serve

- Disinfect frequently touched surfaces at least daily

- Physical barriers at pickup windows and cash registers

- Ensure adequate supplies: soap, hand sanitize, disinfect wipes, masks, no-touch trash cans

- Routine cleaning schedule

Employee Wellness

- Encourage sick or potentially infected employees to stay home

- Require frequent employee handwashing

- Require the use of cloth face coverings among all staff

- Establish flexible work schedules for employees

Operations

- Reduce the use of shared items (menus, condiments, utensils)

- Use touchless payment options when available

- Post signs and messages that promote safe customer practices

Since March, state and local governments have worked with businesses to ensure that precautions are taken for the safety of their residents. Simultaneously, cities are eager to sustain and rebuild local businesses after months of economic distress. With many food establishments forced to shutter or transition to takeout only service, the pandemic has led to widespread job loss in the restaurant industry. Local governments’ handling of this balance between the health of their residents and the strength of their economy has varied significantly across the U.S, depending on state guidance, local regulation, and rates of community transmission of COVID-19.

Analysis

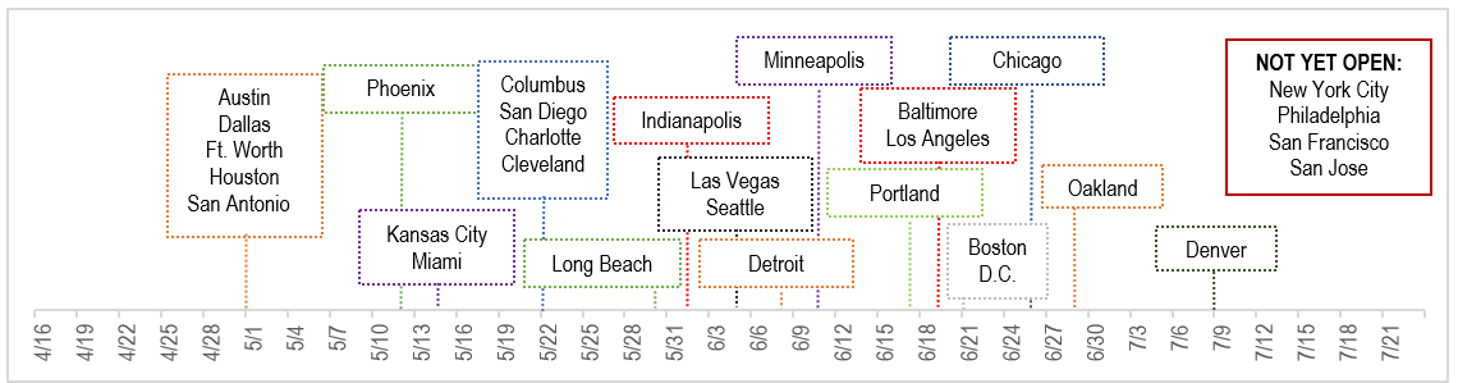

Among the 30 member jurisdictions cities that comprise the Big Cities Health Coalition (BCHC)iii, all but four cities moved into phases of reopening that include indoor dining at restaurants between late April and early July. Some of these cities have since rolled back indoor dining due to an increase in cases and hospitalizations. While restaurants in Texas could reopen indoor dining areas at the beginning of May, other cities like Boston, D.C., Chicago, Oakland, and Denver waited until late June or early July (see Figure 1).2

Tensions between local and state governments have, in some cases, created a barrier to implementing effective policies related to COVID-19. In Texas, Governor Greg Abbott allowed indoor dining to reopen statewide at the beginning of May. Although local officials tried to impose stricter restrictions than the state had issued, state officials declared these local emergency orders unlawful.3 This use of preemption by the Texas state government prevented Austin, Dallas, Fort Worth, Houston, and San Antonio from implementing their own legislation related to indoor dining. Throughout the pandemic, various state governments, like Arizona, Florida, and North Carolina, have similarly preempted localities from enforcing stricter orders than the state. In some cases, cities in states with preemption laws were forced to rescind local measures. In contrast, the state of Maryland governor allowed county leaders to make their own decisions about reopening. The City of Baltimore opted to delay reopening until they met metrics that indicated reduced spread of COVID-19.4

Figure 1: Reopening Date of Indoor Dining By Cityiv

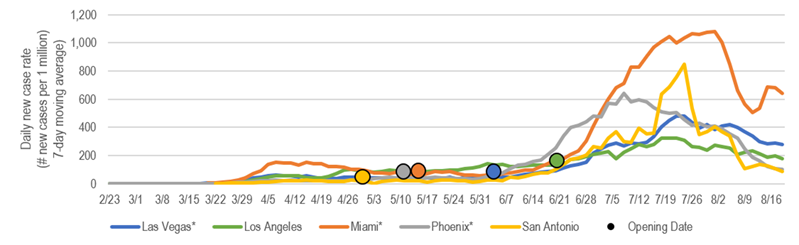

It is important not only to evaluate the indicators that each city used to make reopening decisions, but also to understand how indoor dining impacts the spread of COVID-19. Cities that experienced earlier peaks in COVID-19 cases, like New York City, have been more cautious about reopening indoor dining areas at restaurants. When Phoenix, Miami, Las Vegas, and several cities in Texas reopened restaurants for indoor dining, daily new cases were relatively low, at between 30 and 40 new cases per 1 million residents each day. These cities had not yet faced the uptick in cases experienced by several east coast cities in mid-April. However, two to four weeks after indoor dining reopened, many of these cities saw severe and widespread outbreaks, some experiencing record-breaking single-day new case and death counts (see Figure 2). For example, Miami reopened restaurants for indoor dining on May 15th and began to see an uptick of cases by June 15th. After increases in new cases, Mayor Carlos Gimenez issued a new order to close restaurants except for outdoor dining, takeout, and delivery.5,6

Figure 2: New COVID Case Rates in Select Metropolitan Areas That Have Reopened Indoor Dining

*Operates under a county level health department

Source: COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University

In contrast, New York City, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and San Jose have only allowed outdoor dining at restaurants, continuing to prohibit the use of indoor dining areas.v These cities have paused further restaurant reopening hoping to avoid the spikes in new cases experienced in cities that reopened early. New York City and Philadelphia both maintained more restrictive guidelines around dining than the rest of their state, which may have played a role in the relative stability of infection in these cities. In San Francisco and San Jose, less drastic reopening phases may also have kept case counts from increasing dramatically (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: New Case Rates in Select Metro Areas That Have Not Yet Reopened Indoor Dining

Implications

While there are many factors that play a role in the spread of COVID-19, phases of reopening that included indoor dining and other indoor facilities may have contributed to the widespread outbreaks in late June and early July.8

Rigorous analyses are needed to formally establish the causal impact of indoor dining on outbreaks. However existing descriptive data and case studies of transmission linked to indoor dining suggest that early and aggressive reopening could contribute to increases in cases. The Center for American Progress recently conducted an analysis of the key differences in social-distancing policies, reopening guidelines, and mask mandates implemented by state governments. States that delayed reopening indoor dining areas experienced lower rates of transmission than those that began reopening earlier.9

In making decisions around reopening of businesses and services, local, state, and national governments must weigh health and safety considerations against economic and other demands for their cities. While some cities have followed the guidance from state government, others—including those highlighted here—have made different decisions based on the characteristics of the pandemic in their city – or specific characteristics that put them more at risk, e.g., denser population or disproportionate impact on certain populations.

For example, while Pennsylvania and the Philadelphia suburban counties reopened indoor dining on June 6th, Philadelphia postponed moving into Pennsylvania’s green phase of reopening, only recently announcing the opening of indoor dining as of September 8th. Before doing so, the city intends to meet specific metrics including continued and expanded testing, steadily decreasing case counts and a positive test rate of less than 4%. Case data can therefore inform reopening decisions and, in some cases, returning to earlier restrictions. San Diego County reopened indoor dining facilities mid-May, but the county and the state continued to monitor COVID-19 metrics. Six weeks later, in response to increased case rates, California rolled back reopening of bars, restaurants, and other indoor venues across the state.10

While allowing indoor dining helps support local businesses, COVID data has demonstrated the importance of moving carefully through phases of reopening. Equally important will be continued monitoring of cases and positivity rates and the ability to quickly roll back certain measures if the data indicates. Continued reopening of the U.S. should be done gradually, carefully and with effective communication to the public.

Citation

Connor, G., Vaidya, V., Kolker, J., Li, Ran (2020). Indoor Dining and COVID-19: Implications for Reopening in 30 U.S. Cities. Urban Health Collaborative.

iThroughout this brief, “city” refers to the city itself, the metropolitan area, or the county in which the city resides. Regulations and phased reopening apply at varying levels of government for the 30 cities included in this analysis

iiIt is important to note that some of these cities have since modified their regulations and, in some cases, closed indoor dining areas again.

iiiAdditional information on membership can be found at www.bigcitieshealth.org. Note that some members are county health departments, while others are cities. As already noted, level of data in this analysis also varies.

ivAs of August 31, 2020.

vAs of August 31, 2020, these cities have not yet opened indoor dining. San Francisco and San Jose chose to prohibit indoor dining despite other California cities going forward with reopening. California has since reclosed indoor dining in response to increase case rates across the state. Pennsylvania and New York state allow indoor dining, but New York City and Philadelphia have delayed. Philadelphia is planning to reopen indoor dining on September 8th, with capacity restrictions.

1Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. Considerations for Restaurants and Bars: Guiding Principles. July 17. Accessed 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/organizations/business-employers/bars-restaurants.html.

2Various

3Platoff, Emma. 2020. “Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton warns Austin, San Antonio, Dallas to loosen coronavirus restrictions”, The Texas Tribune. May 12. https://www.texastribune.org/2020/05/12/texas-attorney-general-warn-cities-coronavirus/.

4Davidson, Nestor. 2020. “State Preemption and Local Responses in the Pandemic”, American Constitution Society. June 22. https://www.acslaw.org/expertforum/state-preemption-and-local-responses-in-the-pandemic/

5Local10. 2020. “Coronavirus: Florida reports 7,347 new cases and positivity rate hits single-day high”. July 6. https://www.local10.com/news/local/2020/07/06/coronavirus-florida-latest-case-numbers-covid-19-pandemic/.

6Miami-Dade County. 2020. Press Releases. July 8. https://www.miamidade.gov/global/navigation/prindex.page.

7Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Inf Dis. 20(5):533-534. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1.

8Gamio, Lazaro. “How Coronavirus Cases Have Risen Since States Reopened.” The New York Times, 9 July 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/09/us/coronavirus-cases-reopening-trends.html.

9Gee, E., et al. (2020). A New Strategy to Contain the Coronavirus. August 6. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/healthcare/news/2020/08/06/488775/new-strategy-contain-coronavirus/.

10California Orders Additional Restrictions to Slow Transmissions of COVID-19. 13 July 2020, https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/OPA/Pages/NR20-158.aspx.