Charles Ramsey: I’ve Led Two of the Nation’s Largest Police Departments. Here Are Six Steps to Make Law Enforcement Fairer and More Equitable.

- Ribbon-Cutting Ceremony Marks Official Unveiling of Drexel Station at 30th Street

- Drexel’s Pearlstein Gallery Offers Spring Exhibitions Centered on the Healing Properties of Art and Creative Works

- Express Your Thoughts About Climate Change in the Anthems for the Anthropocene Contest

- 40 Years Ago, Drexel Made Computer — and Apple — History

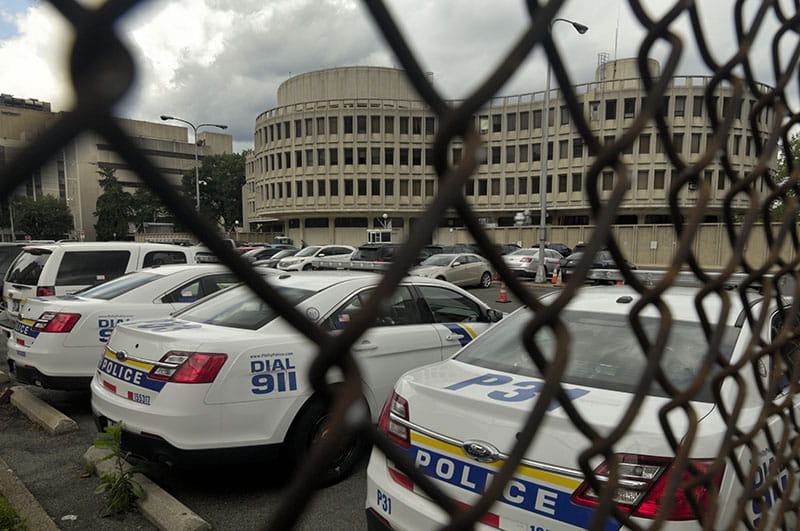

The following essay was originally published in The Philadelphia Inquirer in collaboration with Drexel University’s Lindy Institute for Urban Innovation as part of Rebuilding Philly, a series of commentary articles written by Drexel faculty and professional staff related to the COVID-19 pandemic and racial and economic equity gaps in Philadelphia. It was written by Charles H. Ramsey, a former distinguished visiting fellow of the Lindy Institute for Urban Innovation at Drexel University who served as the commissioner of the Philadelphia Police Department from 2008 to 2016.

Racial bias and other systemic issues exist not only in police agencies but within the entire criminal justice system. These problems are complex and require thoughtful discussion and planning to implement sustainable change that will not jeopardize public safety.

Some are calling for “defunding” the police. Others take it several steps further, calling for disbanding police departments altogether. With violent crime rising in cities across the country, disbanding police agencies, in my opinion, is not a viable option. Whether you agree or disagree with activists and others demanding change, one thing is clear: The status quo is not acceptable.

Whatever changes police administrators make in the future must include meaningful input from the community. Those changes will require progressive police leaders who can adapt to the unforeseen challenges that await them and who are willing to listen — both to the voices of community members and the officers who work for them.

Solving the issues confronting the criminal justice system goes beyond merely redirecting funds. Drawing on my experience having led two of the nation’s largest police departments — here in Philadelphia and in Washington, D.C. — I’ve developed a few ideas for how law enforcement can meet the demands of this moment:

- Police agencies must better recruit and hire a diverse workforce — people with the psychological makeup and analytical skills necessary to handle the trauma and complexity associated with policing.

- Cities must stop giving away management rights in collective bargaining agreements that make it difficult to hold officers accountable for their actions.

- Educational programs that emphasize concepts like fair, impartial, and constitutional policing and procedural justice must become a part of police training.

- It is equally vital that officers learn the damaging history of policing in America and the impact on the poor and communities of color.

- Congress must act and establish national standards that cover the use of force, training, leadership development, and certification for police officers, deputy sheriffs, and police agencies.

- We must all work together to rid policing of those that abuse their authority and treat community members with disrespect. Establish a national database containing the names of officers who have been found guilty of serious misconduct or who have been fired to prevent them from seeking employment in other law enforcement agencies.

Police officers take an oath to “serve and protect;” those words mean much more than protecting life and property. The pledge also carries with it the tremendous responsibility of protecting the constitutional rights of all Americans — of safeguarding the very freedoms that we cherish and that set us apart from so many other nations on Earth.

Neither the police nor the members of our communities should accept the notion that overly aggressive tactics that strip away individual rights are somehow the only way to solve our crime problems and create safer cities.

Drexel News is produced by

University Marketing and Communications.