Drexel’s Center for Cultural Partnerships Helps Build the National Museum of Industrial History

- Ribbon-Cutting Ceremony Marks Official Unveiling of Drexel Station at 30th Street

- Drexel’s Pearlstein Gallery Offers Spring Exhibitions Centered on the Healing Properties of Art and Creative Works

- Express Your Thoughts About Climate Change in the Anthems for the Anthropocene Contest

- 40 Years Ago, Drexel Made Computer — and Apple — History

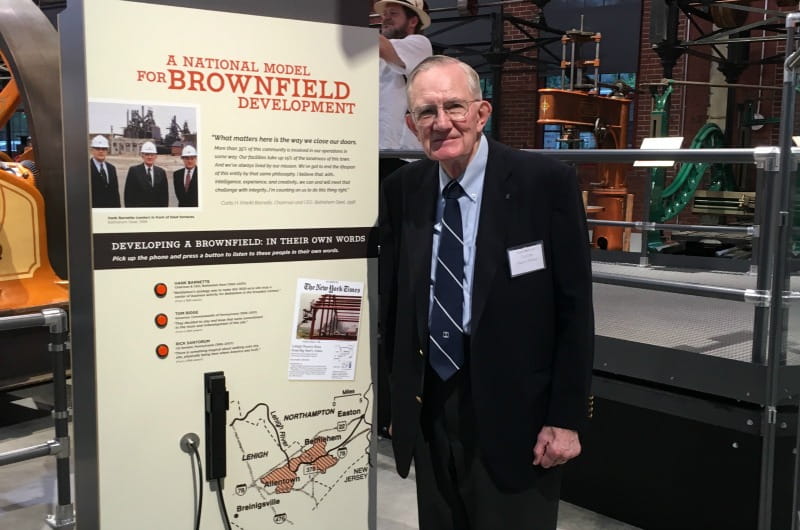

Thanks to the help of Drexel’s Center for Cultural Partnerships, the National Museum of Industrial History (NMIH) opened in August in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, after being first proposed in the ‘90s.

Vice Provost and Lenfest Executive Director Rosalind Remer was given just over a year to help complete what has taken about two decades to accomplish. She pulled together a team to design the museum’s layout; curate the exhibits; develop all exhibit texts and graphics; research and find content like videos, images and historic quotes and texts; and, most importantly, get the museum ready for the public. Because of her guidance and expertise, the daunting task was not only completed, but was finished on time and on budget.

“It was one of the most challenging projects that I’ve ever worked on, but I’m very proud of our work and the role Drexel played,” said Remer.

The idea of the National Museum of Industrial History dates back to the late ‘90s, when Bethlehem Steel was facing its eventual collapse and its CEO, Curtis H. “Hank” Barnett, wished to preserve the sites and the story of the powerful manufacturing company. An affiliation with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History widened the scope of the future museum — instead of solely focusing on the legacy and impact of Bethlehem Steel, the Smithsonian would supply complimentary manufacturing artifacts from its industrial history collection to tell the story of the Industrial Revolution, the rise of machinery and its effects on American history and society.

However, the museum remained in the planning stages for about 15 years until May 2015, when Amy Hollander was hired as the museum's executive director and was tasked with the job of opening the museum. Helping her was Brent Glass, former director of the National Museum of American History, who recommended bringing in Remer to produce the exhibition.

“Ros is a rare public historian who can translate academic research into a publicly accessible language,” said Glass. “She has an extensive network of museum professionals in Philadelphia and other locations around the country. Finally, she can operate within a tight schedule and even tighter budget and that is exactly what we needed for NMIH.”

Remer came on board in August 2015, exactly one year before the museum was supposed to be open.

“When I was telling people in the museum industry about the timetable, everyone was looking at me like I was crazy,” said Hollander. “We really needed a team leader we could trust to put together the right combination of professionals to create an authentic, powerful and interactive experience on a tight schedule and a tight budget.”

Remer, as chief interpretive planner, suggested working with outside design and fabrication teams to curate, design and build the exhibitions. In December, she chose which teams she would work with: a design team to help create the look of the exhibit, and a fabrication team to build everything from ramps to murals to mounts for the objects.

In January and February, Melissa Clemmer, a project manager and certified interpretive planner who works with Remer in the center, produced the interpretive plan for the exhibit, worked with NMIH staff and the design/fabrication team to develop all the exhibit elements and produced all the final content, which included research, writing and editing.

“Our role was to understand enough to accurately digest and convey fascinating information for the general public,” said Clemmer. “This project was interesting for me personally because I got to learn new things — everything from what a flywheel does to how steel is made to how Jacquard looms work to how propane is produced.

All images, text, video and plans were sent to the design team to create and the fabrication firm to build. The finished project was finished and installed in mid-July and the museum greeted its first visitors in August.

Housed on a brownfield site in Bethlehem Steel’s 18,000-square-foot 1913 Electric Repair Shop —an artifact in its own right — the museum tells the story of industrial innovation and manufacturing in American history and society. Bethlehem Steel and the Bethlehem community it grew out of are also featured heavily in that narrative.

“The museum is a way to recognize new developments for the community while still honoring the community’s industrial heritage,” said Hollander, who has seen community members and tourists of all ages come together to learn about American industry in Bethlehem and across the country. “We want to educate the public about past American innovation and inspire a new generation of visionaries, makers and entrepreneurs.”

Museum visitors can also learn from artifacts from the National Museum of American History’s industrial collection, such as the machines and pieces originally displayed at the Centennial International Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876. Other artifacts include a World War I cannon, a propane hot air balloon and a silk loom that made curtains for the White House from the Herbert Hoover presidency during the Great Depression to the Clinton administration in the ‘90s.

The museum’s opening was a success, as was the public’s response to the artifacts and the history it told. Bethlehem Steel’s last CEO, who originally had the vision for the museum and has become a huge proponent of remodeling the space to benefit the community, was very happy with how it turned out, as were the museum’s leaders and benefactors.

For the center, the project represents a connection to a cultural organization that’s brand new, as opposed to its other ties to established organizations. The center has already partnered with local institutions on a major heritage tourism project in Philadelphia and with the African American Museum on strategic planning. This fall, the center will partner with the Reading Terminal Market on an interpretive planning class for graduate students in the Museum Leadership program and undergraduate history students and a museum space planning studio for architecture and interiors students.

“The NMIH project was less characteristic of what we would do at the center, since it wasn’t interdisciplinary across colleges and didn’t use any students due to the time-crunch and the nature of the project,” explained Remer. “But it was a consulting project that brought in a significant grant and it was a wonderful way to promote the center and what we’re capable of doing when faced with a unique challenge.”

This piece first appeared in Drexel Quarterly's Fall 2016 issue.In This Article

Drexel News is produced by

University Marketing and Communications.