Could Death Rates Have Swung the 2016 Election?

By Frank Otto

By Frank Otto

Significant increases in the death rates of white, middle-aged people over the last 15 years appear to be tied to increases in Republican voting that helped lead to Donald Trump’s election in 2016, according to a new study led by a Drexel University researcher.

Examining data for white people between the ages of 45 and 54, Usama Bilal, MD, PhD, and his co-researchers found that Trump was more likely to win counties where the middle-aged white death rates increased significantly from 1999 until 2016 than his Democrat opponent, Hillary Clinton.

“We believe that counties where mortality has been increasing in the last decade have seen higher degrees of social disruption — such as changes in employment availability, health care accessibility and/or poverty levels — leading to changes in voting patterns,” Bilal said.

On average, a 15.2 death increase per 100,000 middle-aged white people was tied to a 1 percent vote swing for the Republican presidential candidate in 2016, the study showed.

“Michigan, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin had less than a 1 percent difference between the two parties in the 2016 election,” said Bilal, a post-doctoral researcher at Drexel’s Dornsife School of Public Health. “Of these four states, the GOP won Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, allowing them to secure the electoral college vote.”

Bilal, along with Emily Knapp, of Johns Hopkins University, and Richard Cooper, MD, of Loyola University (Chicago), started thinking about a study looking into this on election night in 2016, when Bilal was a doctoral student at Johns Hopkins. Public health scientists have noted often that white mortality rates appear to have changed in recent years. So Bilal and his co-authors studied this population in the context of another study that attributed these deaths to the increased availability of prescription opioids, drug overdoses and weaker public assistance programs.

“We entertain the idea that mortality itself is a marker of underlying social conditions that are often reflecting in changing political landscapes,” Bilal said of the study that was published in Social Science and Medicine.

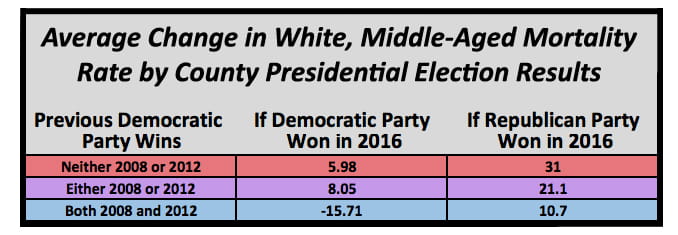

Using data from 2,764 counties (roughly 91 percent of the counties in the U.S), Bilal and his team found that counties that voted Republican, after being Democrat for 2008 and 2012, showed an average increase of 10.7 deaths per 100,000 middle-aged white residents over the last 15 years.

But if counties that voted Democrat in 2008 and 2012 stayed Democrat for 2016, the death rates there actually declined over the last 15 years by 15.7 per 100,000, on average, the study discovered.

The researchers didn’t just focus on mortality rates and their potential affect on vote-swings. They also took a look at whether vote swings were more evident in counties with wider health inequalities.

“In our study, health inequality refers to the difference in life expectancy between the people in the top 25 percent of income versus the bottom 25 percent,” Bilal explained.

In any county that had gone Republican, just once, in 2000, 2004, 2008 or 2012, there were markedly higher levels of health inequality. For counties that voted Republican in 2008 and 2012, the study showed almost 30 percent wider inequalities.

But that doesn’t mean things were completely even in Democrat counties. On average, the difference in life expectancy was 7.23 years in Republican counties, but still 6.6 years in Democrat counties.

“Health inequalities are the sign of a society that does not do enough to protect the public’s health, where poorer people have less access to health-promoting resources (such as healthier foods, safer neighborhoods or even health care) and are more exposed to environmental hazards (such as pollution, crime or unwalkable neighborhoods),” Bilal said “Our research has shown that the Republican party vote share increased in areas where these health inequalities are wider.”

All of the mortality and inequity results were consistent when the researchers limited their data to six of the key states that helped flip the 2016 election to Republicans: Iowa, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin and Florida.

More work is needed (potentially studying the United Kingdom’s Brexit or the rise of far-right groups in European elections) to get a better idea of the strength of associations, but Bilal feels the study definitely shows that “politics and health are intertwined.”

“We should consider public health as a potent marker of social upheaval,” Bilal said. “Moreover, the health of the electorate — especially those middle-aged folks who are dying prematurely — is central to a democracy.”