Moss Effective in Pinpointing Air Pollution Sources

By Frank Otto

By Frank Otto

With air quality monitors few and far between in cities, a study in Portland, Oregon, proved that moss can be an effective tool for identifying sources of atmospheric pollution.

The study of naturally growing tree moss at more than 300 sites across the city was a joint work between the United States Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service and researchers from Drexel University’s Dornsife School of Public Health.

Moss has been established as a bio-indicator for chemicals in the air for some time, but the study used the moss in a brand-new way.

“What’s unique about this study is that we used moss to track down previously unknown pollution sources in a complex urban environment with many possible sources,” said Sarah Jovan, a research lichenologist with the Forest Service.

Jovan was joined by Geoffrey Donovan, Demetrios Gatziolis, Michael Amacher and Vicente Monleon from the Forest Service, and Igor Burstyn and Yvonne Michael from Drexel as co-authors for the study, which was published in Science of the Total Environment under the title “Using an epiphytic moss to identify previously unknown sources of atmospheric cadmium pollution.”

Although cities often use air quality monitors, the devices are costly and usually stationed too far apart to determine the points from which pollution might originate. Compounding the issue, reductions in funding in recent years have only decreased the number of monitors.

With that in mind, the research team decided to sample naturally growing Orthotrichum lyelli moss, to investigate whether it could be an inexpensive complement to monitoring. The samples were taken from more than 300 locations across Portland, using a modified randomized grid-based sampling strategy designed by Drexel researchers.

“We were curious to see whether a new method of assessing air pollution would reveal sources pollution, and could work just as well as established methods but at a fraction of a cost,” said Burstyn, an associate professor of Environmental and Occupational Health as well as Epidemiology and Biostatistics in the Dornsife School of Public Health at Drexel.

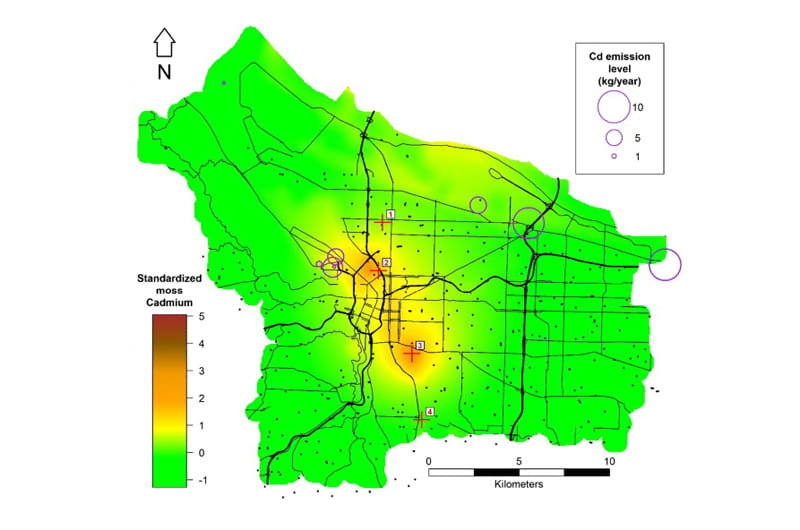

Sampling occurred over several weeks in December 2013. When they were tested, the samples indicated that there were two distinct hotspots for cadmium. These fell outside of the area where cadmium was expected to be higher, where companies with permits for cadmium emission were located.

Within each hotspot, there was a stained glass manufacturer that used cadmium — which is sometimes used in pigments — in production. Both companies were not required to have the cadmium emissions permits and were previously overlooked when accounting for potential atmospheric cadmium in Portland.

Outside of one plant, the moss samples confirmed high levels of cadmium that had been detected by air monitors several years earlier, measuring cadmium at 12 times Oregon’s benchmark for the metal.

Two years after the initial collections, moss samples were again taken from the area of one of the plants, turning up similar results. The Oregon Department of Environmental Quality also placed an air monitor near the plant. Readings from air monitors corroborated with the moss samples and confirmed cadmium at levels 49 times higher than Oregon’s benchmark.

Additionally, other heavy metals like arsenic and selenium — detected in both sets of moss samples — were confirmed by the air monitor. Arsenic and selenium are also sometimes used in stained glass production.

With the air monitor results affirming what was found in the moss samples, researchers concluded that this method of analysis served as a reliable indicator to pinpoint areas of elevated pollution levels. Cities could potentially map sources of pollution using naturally growing moss.

In This Article

Contact

Drexel News is produced by

University Marketing and Communications.