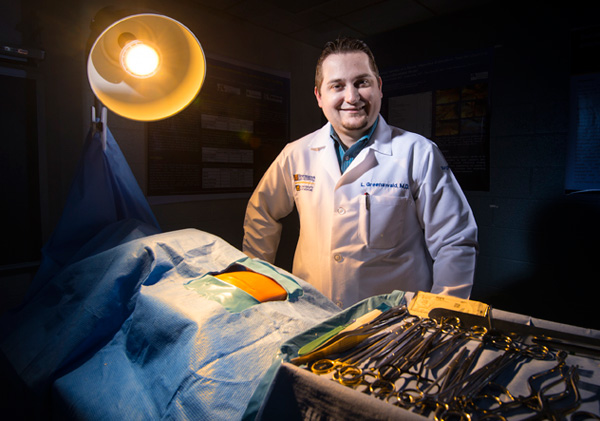

Dr. Fix-It: Lawrence Greenawald, MD, Resident

Enter the lair of Lawrence Greenawald, triple dragon (Drexel BS ’06, MD ’10, surgical resident), and you can’t be sure who or what you will find. For this is the realm of simulation: populated by virtual patients and mixed-reality humans. If not otherwise engaged, TraumaMan might even drop by. Here, Greenawald and colleagues in the Laboratory for Simulation & Surgical Skills are creating advanced tools and constructs for teaching not just future surgeons, but others who practice medicine. With his training and passion for surgery, the ability to see where something can be improved runs deep — and this includes how students learn to become doctors.

After completing his first two years in the Drexel/Hahnemann General Surgery Residency program, Greenawald shifted gears to spend time as a research resident, an option four to six surgical residents avail themselves of each year. His mentor is D. Scott Lind, MD, professor and chair of the Department of Surgery. Lind, who began developing virtual and mixed-reality patients more than a decade ago at the University of Florida, has a national reputation for innovation in medical simulation. Under his leadership, Greenawald, with other residents and faculty, has been developing and validating simulation models for the surgical curriculum.

For most doctors, even of his generation, Greenawald points out, the first time they performed a surgery was when “a patient in the middle of the night needed it done.” As new approaches, such as minimally invasive surgery, were developed, techniques for training in those methods were developed as well. But open surgery? That was learned in the operating room. And although the majority of abdominal surgeries are still open surgeries, there has been no validated tool to assess fundamental surgical skills. Now, Greenawald, Lind et al. have presented such a tool. The novice is videotaped performing a basic open laparotomy on a simulated abdomen. Blinded evaluators review the video and score the student on 16 essential steps.* Greenawald sees tremendous opportunity for students to gain experience before they enter the OR. “The benefit of simulation is that you get their hands to start working,” he says. “Then you can teach them the fine points later.”

Greenawald and Lind have been working on several collaborations with the School of Engineering, including an enhanced computerized model of a prostate examination; a mixed-reality patient with simulated tumors in the breast; and a project using computer algorithms to detect surgical items left behind after a procedure.

Looking into the mind of the surgeon, or student of surgery, is the focus of another interdisciplinary research program. Functional near-infrared imaging is used to measure blood flow in the frontal cortex and assess cognitive workload. With this technology, not only could you examine changes associated with learning procedural skills, Greenawald explains, but you could examine two people who have had exactly the same training and see if there are differences in how the work — or time of day — affects them. “People theorize about this,” he says, “but there have not been any physiologic measures.” Potentially, the results could be used to optimize surgical training regimens and surgery schedules.

The Department of Surgery has been fortunate to enjoy a history of working with the College of Engineering, Greenawald says. “Our lab has a great collaborative group across colleges and schools,” he adds. “Our attitude is that our best chance of success comes with active and open collaboration. If you approach it with that attitude from the outset, you’ll get lots of results. We’ve built some very good relationships, which we’re grateful for.”

Greenawald approaches teaching with the same collaborative spirit. “The meaning of the word doctor is ‘teacher,’” he says. His mother is an educator and his father taught for a time as well. Sharing what one has learned is part of doing one’s job. “I really enjoy working with my junior residents, with medical students, and sharing the knowledge I’ve been able to gather,” Greenawald says.

A lifelong resident of Doylestown, Pa., Greenawald first came to Drexel in 2002 as an undergraduate. He wanted to be in the city for college and was intrigued by Drexel’s commitment to applied science, evidenced by the co-op program. He was also very interested in the school’s partnership with MCP-Hahnemann. Greenawald says, “I felt like [Drexel] would not only foster my pre-medical education, but give me the chance to transition to medical school and succeed in that.”

Although Greenawald liked engineering, he focused on biology and chemistry as an undergrad. Medicine ultimately appealed to him for two reasons. First, “You spend your days helping people,” he explains, “and hopefully effecting some positive good in the world.” Second, he enjoyed the intellectual challenge posed by medicine.

Greenawald’s professional path began to reveal itself in Gross Anatomy Lab (coordinated by Dennis DePace, PhD) during his first semester as a medical student. “That’s where I fell in love with the anatomy of the human body — how it works and how it can fail,” he explains. “That’s obviously the first part of becoming a good surgeon, because you have to understand how the body works, how it can fail, how you can fix it.”

Professor Michael Weingarten, MD, a vascular surgeon and “passionate educator,” was “probably the biggest influence” for anyone considering surgery, Greenawald says. Another faculty member had good advice for him as well. During the third-year clerkships, Samuel Parrish, MD, then associate dean for student affairs, recommended that students take something else into account when considering potential areas of specialization: “It may not necessarily be what interests you most, but who are the people you want to work with the rest of your life,” he recalls Parrish saying.

For Greenwald, those people were, without a doubt, surgeons. As a child, he says, he was always “taking things apart and putting them back together.” He once considered this curiosity the sign of an engineer; now he believes you also need this investigative drive as a surgeon. Surgery, he says, “especially the how-to-fix-it part, is the ultimate representation of that challenge.”

The pragmatic nature of surgery also greatly appeals to Greenawald. “You evaluate a patient who comes in with a problem. Within an hour or two, you could be fixing said problem in the operating room.” He elaborates: “Surgeons have the perception of being first and foremost problem-solvers. We like to find something and do something about it. The patient’s happy. We’re happy. That has its own reward.”

In June, Greenawald will leave his post in research and return to the hospital to complete his residency. He credits Lind — and is grateful for his mentorship — with getting him “attuned to how academic surgery works.” When he accompanied Lind to the annual meeting of surgery program directors, Greenawald notes, “there was basically a line of people waiting to greet Dr. Lind. Half the people there seemed to be surgeons he had trained himself.”

Whether it is as a surgeon, a researcher or an educator, Greenawald wants to understand how things work so he can make them better.

Note:

* Lawrence Greenawald, MD; Mohammad Shaikh, MD; Jorge Uribe, MD; Faiz Shariff, MD; Barry Mann, MD; Christopher Pezzi, MD; Andres Castellanos, MD; D. Scott Lind, MD. “Construct Validity of a Novel, Objective Evaluation Tool for the Basics of Laparotomy Training Using a Simulated Model.” This work was funded by a grant from the Association for Surgical Education and the Association of Program Directors in Surgery.

Back to Top