Globally and locally, our cities need urban transport policies that impact health and equity

This World Environment Day, we highlight the importance of studying and sharing insights from policies

Posted on

June 5, 2018

By: Daniel Rodriguez, PhD and Xize Wang, PhD

Department of City and Regional Planning

University of California, Berkeley

On June 5, we celebrate World Environment Day, a global call for action and awareness around the many challenges facing our planet that must be solved collaboratively and through smarter policies. This year, as urban health researchers and city planners, we want to bring attention to our urban environments, policies, and administrative decisions and their role in impacting health. The way we design our cities influences our ability to drink clean water, breathe clean air, be social, access medical and recreational services, and live a fruitful and rewarding life. Many aspects of cities that influence health include infrastructure: the places we can get to by walking or public transportation, our proximity to polluting and noisy traffic, or our ability to drink clean water.

Policies that determine how and where the infrastructure is implemented, how much it costs to use it, and when, also have enormous impacts on urban health. In this blog, we highlight the importance of one such type of these policies: fares to use transit systems. Transit systems can include trains, buses in exclusive lanes, or the regular buses that traverse many city streets.

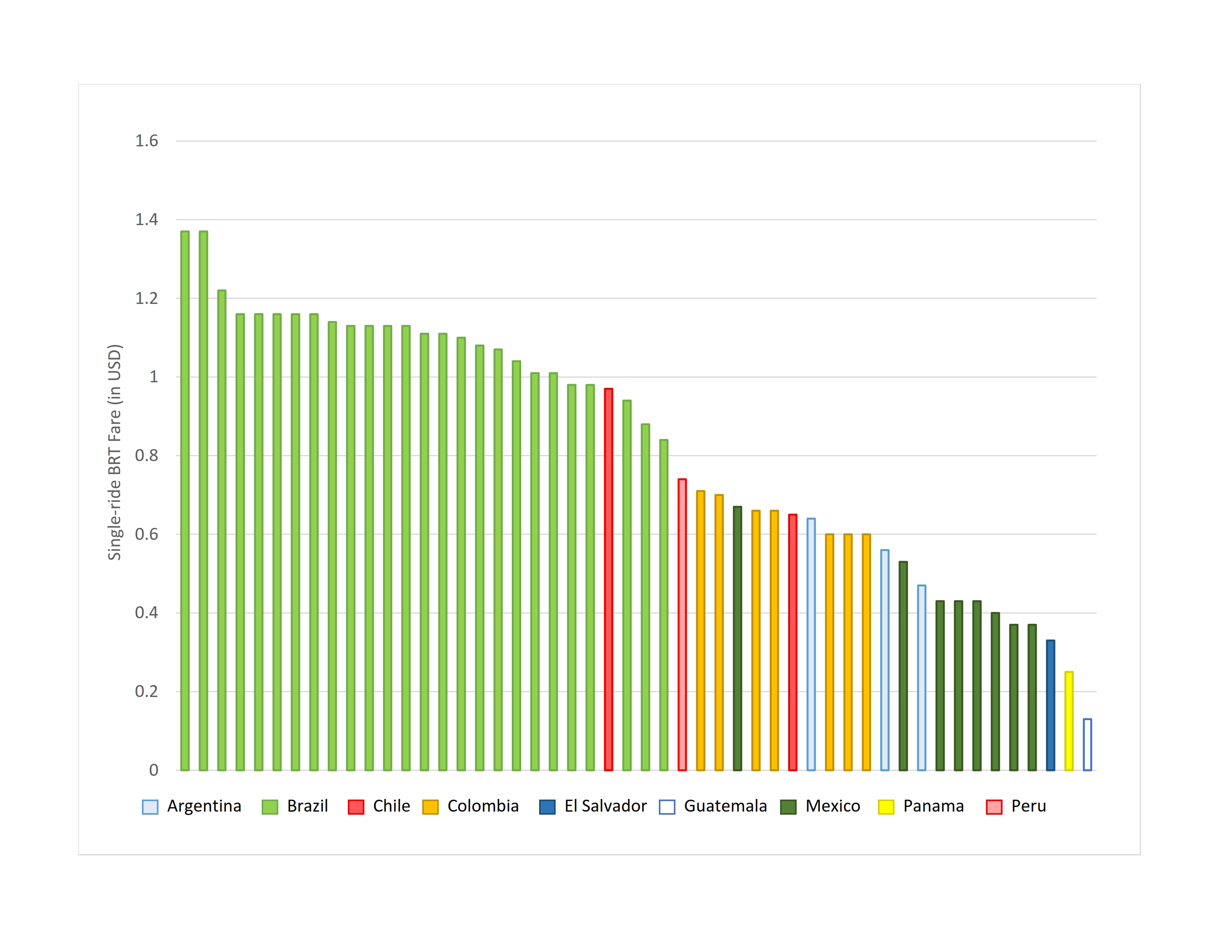

Through the emerging research of the Salud Urbana en América Latina (SALURBAL) team, we've identified important variation in the cost of using public transportation in Latin American cities (Figure 1). This represents the one-way fare for an adult using Bus Rapid Transit (BRT), a bus-based public transit system seen in large cities throughout Latin America and other parts of the world, such as Asia, Europe, and the United States. Although in some cities youth, older adults, or the very poor get fare subsidies, the fares shown tend to be a good representation of the cost of using public transit in these cities.

Figure 1 - One-way bus rapid transit fare for 50 Latin American cities (in USD)

Source of data: SALURBAL Built Environment Core

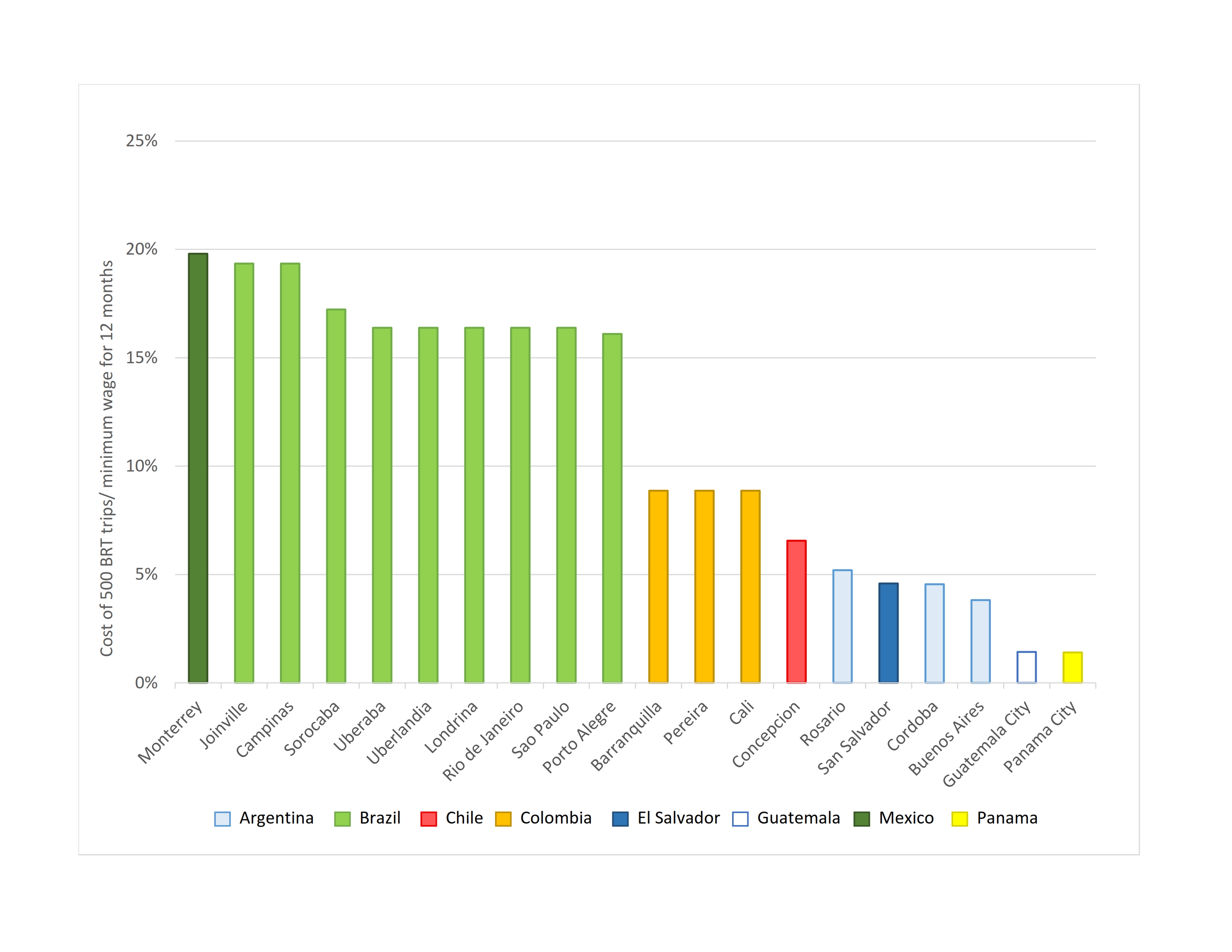

In some cases, the cost is very high. Consider a low-income resident -- perhaps earning minimum wage, and making a single round trip a day (going to and from work) using BRT. The person would make this trip about 250 days each year. For São Paulo, whose transit fare ($1.21 per ride) is the 8th highest out of 50 Latin American cities, this hypothetical person would pay about 16.4 percent of the personal minimum wage solely getting to and from work. For Latin American cities, this share could go as high as 19.8 percent (Figure 2). If that person had to transfer between bus lines or from the BRT to other forms of public transport, such as a metro, the cost of a one-way trip may be even higher. Other trips - to the market, to visit a relative, to a medical specialist - would create additional costs. This simple example shows the importance of policy, in this case fare policy, in influencing people’s ability to reach destinations in cities. As part of the SALURBAL project, we’ve begun to identify other transportation policies, like the cost of gasoline, the availability of parking, or the presence of bicycle lanes, that are likely to impact health in a variety of important ways. The policies and infrastructures are likely to impact how people travel, where they travel, and how often, as well as the secondary impacts that such travel may have on the rest of the urban population, such as emissions of air pollutants, noise, and travel delay.

Figure 2 – Estimated annual BRT fare cost as a percentage of 12-month minimum wage, top and bottom 10s for 50 Latin American cities

Figure 2 – Estimated annual BRT fare cost as a percentage of 12-month minimum wage, top and bottom 10s for 50 Latin American cities

Furthermore, as incomes change the importance of these policies will also vary. The health and wellness of high-income residents is not likely to be affected by transit fares. But for a low-income individual, these policies are likely to have significant impacts. That’s why these policies both contribute to health disparities in the population, but also have the potential to be meaningful sites for intervention to improve equity.

Given that high income inequality is a great social challenge in Latin American cities, policies that address both the health of residents and disparities in health outcomes would yield a double benefit. Many countries in the region have already begun to implement promising transportation policies that have the potential to improve social equity, health, and empower communities through improved safety, mobility, and connectivity. For example, La Paz’s cable car system, Mi Teleférico, and Medellín’s Metrocable connect low-income, informal communities to city centers were employment opportunities and services are located and have been shown to decrease violence and increase employment. Other cities in Brazil are actively considering making their public transportation fare free in order to provide basic mobility for the urban poor. Studying policies that are working well can offer insights and strategies to be adapted in other cities, in Latin America and other parts of the world.

This World Environment Day, we highlight the importance of urban policies that may at first glance seem unrelated to health, yet are likely to have an important impact on the health and wellness of residents. For updates on our research connecting infrastructure and policies to health outcomes and health disparities in Latin America, follow the SALURBAL project.

--

This post was written by Daniel Rodriguez, PhD and Xize Wang, PhD as a contribution to Cities, Sectors, and Health, run by the SALURBAL Project. To contact the blog or learn more about the SALURBAL project email salurbal@drexel.edu