It is not unusual that a renowned professor of engineering should suddenly decide to teach a course on the Holocaust. For many Jewish scholars, it is the fulfillment of a sacred duty to pass the wrenching lessons of World War II on to a new generation. What is unusual here is that it happens to be this professor, Peter Herczfeld, a survivor who was often encouraged to teach about the Holocaust but never, before this point, much wanted to.

Dr. Peter Herczfeld

This term, which is likely to be his last at Drexel after 52 years as the College of Engineering’s Lester A. Kraus Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECE), Herczfeld is teaching “The Holocaust with Personal Observations of a Survivor” in the Pennoni Honors College. In his class, 17 students hear about the Holocaust from the perspective of a Hungarian, about a mother’s cool composure in the face of the Nazis, about a father who died at Auschwitz, and about the lives of Jewish Hungarians—one of the most assimilated populations in all of Europe—leading up to WWII.

Meeting each Monday afternoon, the course is a three-hour amalgam of history, politics, memory, and family life from the perspective of someone who was just seven years old at the time of the Holocaust. Herczfeld brings the history to life through books and movies he has carefully selected as foundation stones: Fateless, by Istvan Kertesz; “1945,” a movie set in post-WWII Hungary; Night, by Elie Wiesel;” and Hannah Arendt’s account of the Eichmann trials, among others.

Still, it is the weight of personal memory that gives his course its ballast.

“You try to put it out of your mind, what you experienced, and you don’t want to come back to it. But I had a very good friend here at Drexel, the late Dr. Bob Fischl, who was in the department. We were the best of friends. We used to have coffee every morning in my lab,” says Herczfeld. “He was a survivor, and his kids arranged that he would be interviewed by the Spielberg Foundation. He came in one day and told me what he had talked about.

“Our stories were so similar, especially one about how they were stopped by the Gestapo and managed to get through. That was the same thing with me and my mom. So I thought, okay, let me continue with that.”

“As liberal democracy is fading and nationalism is on the rise, these issues are increasingly relevant. I don’t want to make a political point, but still, it should be noted: this is how it happened before.”

Peter Herczfeld

During the first meeting of his class several weeks ago, Herczfeld was surprised by the diversity in the honors college classroom. There are students not just the US and Europe but from India and Pakistan—groups whose received lessons about the Holocaust may be markedly different from others. This necessitated a slight departure from his usual modus operandi.

“I used to tell my graduate students, don’t overdue the number of slides,” says Herczfeld. “But in this case, I prepared a lot of slides. I’m struggling with, how much do they know? How much do I want to tell who Hitler was? I don’t know how much explanation they need.”

The course is structured around several goals Herczfeld feels are essential to the success of the message he wants to impart. Students, he says, should understand the forces that made the Holocaust possible. And he wants to join the effort to make certain it is not forgotten and does not happen again. Early lectures in the course included information on isolationism, how the “enemy” was defined through a vigorous propaganda campaign, and how emergencies were manufactured to keep the citizenry in fear and in check – all parallels with current developments that Herczfeld believes are important to emphasize.

“As liberal democracy is fading and nationalism is on the rise, these issues are increasingly relevant. I don’t want to make a political point,” he says, “but still, it should be noted: this is how it happened before.”

A Childhood in Hiding

Herczfeld was born in Budapest, Hungary in 1936, the only child of a Stephanie and Imre Herczfeld. In fact, he points out that there were many “only” children growing up around him. Of all his childhood classmates and friends, only two had siblings. “By then the war had started,” he says, “and no one wanted to have children.”

His father was in a forced labor camp attached to the Hungarian Army. Although Jewish Hungarians were not permitted to have guns, they were conscripted to support the war effort through digging ditches and other forms of manual labor. In that capacity, Imre Herczfeld was eventually sent to the Russian Front. He returned home briefly in the summer of 1944 for a medical procedure, but was almost immediately sent back. During that return trip, his train was diverted by Adolf Eichmann to Auschwitz.

Peter Herczfeld and his grandchildren visited the Raoul Wallenberg Memorial Park in Budapest. They are standing at the Tree of Life, a sculpture with the names of Jews who perished in Auschwitz, in front of the leaf for Peter's father, Imre Herczfeld.

In the interim before his departure, Herczfeld’s father obtained false papers for his family that required his young son to memorize and use a different name and personal narrative when he was speaking with anyone outside of the family. The smallest mistake, he says, could have led to discovery. By continually moving from one relative’s apartment to another throughout Budapest, Herczfeld’s mother managed to keep the two of them safe, using the falsified papers so adroitly that their true identities as Jewish citizens were never uncovered – even when they were stopped in the streets and interrogated by German soldiers.

“My mom kept covering up my eyes because if anybody was not for the Nazis, they’d hang them from lampposts, and my mom didn’t want me to see,” says Herczfeld. “But of course, I did see.”

One of his uncles worked for a liberal newspaper in Budapest and was privy to information very few others in the Jewish community had. He regularly warned Herczfeld’s mother not to listen to proclamations and not to follow official orders as if they were the only course of action. His warning was one of the reasons they narrowly avoided joining so much of the Jewish citizenry in the ghettos.

“My mother spoke some German. So when we were stopped about showing our papers, she never, never talked to the Hungarian fascists who were carrying out the Germans’ orders. She always spoke to the Germans. Always. My mom saved me. She was able to do lots of things.

“The real heroes of the war were the moms.”

Conversation That Bolsters Learning

Each week in class, Herczfeld asks students to raise three questions for discussion. It’s an experiment, as he has never taught a course in this manner before despite five decades on the College faculty. It seems to be paying off. The larger history is passed on, but what students most want to know about is his own history. Among the questions students have asked are: why didn’t more Jewish citizens leave before Hitler came to power; why were they singled out and not any other major religion; did the Jewish Europeans who made it to America try to raise awareness; how many companies made use of slave labor during the Holocaust, and did they face any repercussions after the war?

“If it comes up in class, I will talk about it,” says Herczfeld. “It was a traumatic experience, but I really prepared myself for this. If you don’t, you don’t survive thinking about it.”

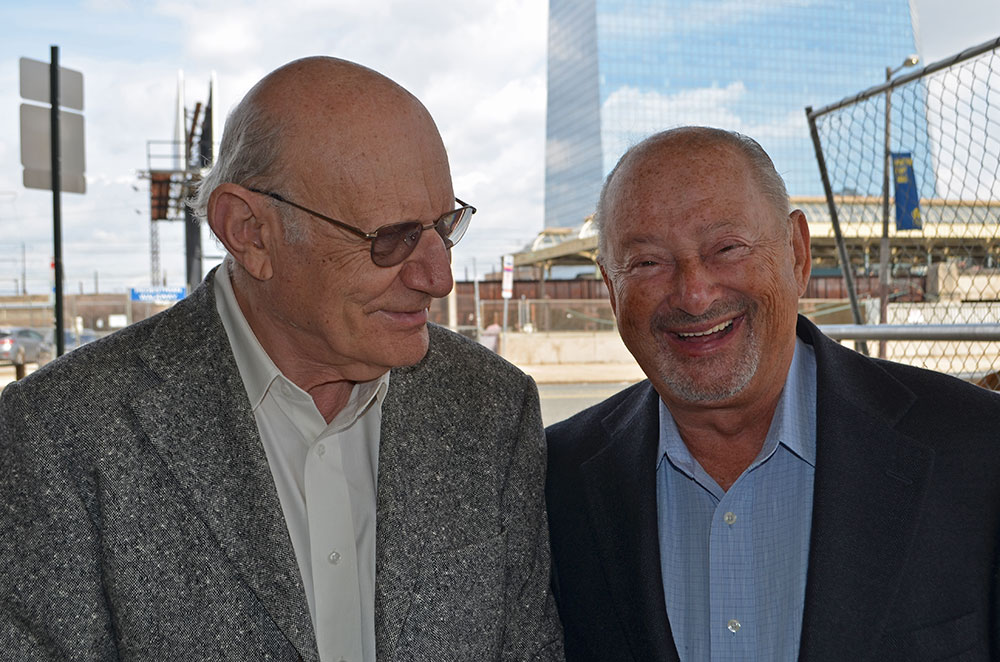

Dr. Peter Herczfeld (right) with his childhood friend Dr. Peter Kenez

One of the ways Herczfeld will pass on his material is by sharing it with a childhood friend, Dr. Peter Kenez, a historian and scholar of Russian history. Herczfeld and Kenez escaped to Vienna from Hungary together in 1956 before coming to the United States and finding their footing as academics. Kenez, who is now professor emeritus at the University of California, Santa Cruz, recently visited Pennoni Honors College to give a lecture to Herczfeld’s students about his own experiences as a survivor.

Herczfeld received his BS in Physics from Colorado State University, and an MS in Physics and PhD in electrical engineering from the University of Minnesota. He came to Drexel in 1967. Throughout his career, he has received numerous teaching and research awards. He was director of the Center for Microwave-Lightwave Engineering at Drexel, and has published in over 500 technical publications. Herczfeld has mentored 35 doctoral students and 100 MS students.

At the invitation of Dr. Paula Marantz Cohen, dean of Pennoni Honors College, Herczfeld will also archive his course notes and record his lectures, with slides, at Drexel Online so that the material can be saved at Pennoni. Cohen has hopes of using the coursework again.

“I was excited when I heard that Dr. Herczfeld, who has had a distinguished career at Drexel in electrical engineering, was interested in teaching a course on the Holocaust based on his own personal experiences,” said Cohen. “He had recounted to me his ordeal as a child in Hungary during World War II. I knew that he could supply a unique context for our students about this tragic historical event.”

Asked if he would consider teaching the course again, Herczfeld was skeptical, even though his children and grandchildren favor the possibility as a way of honoring both his own life and those who did not live beyond WWII. Teaching the material, he says, is emotionally and physically exhausting. But the recent experience of having one of his students stay after class to talk with him in depth revived his sense of what he calls an “obligation.”

“Many people who experienced this took a long time to write about, and many of them couldn’t even survive writing about it,” he says. “But it’s an obligation. The younger generation doesn’t know much about the Holocaust, and that is one of the responsibilities we have as survivors: to make sure it’s not forgotten.”