For the first time in six years, Drexel University will field an entry in the Formula SAE International Collegiate Design Series, with undergraduates in the College of Engineering building a formula-style racecar from scratch to compete against teams from around the world.

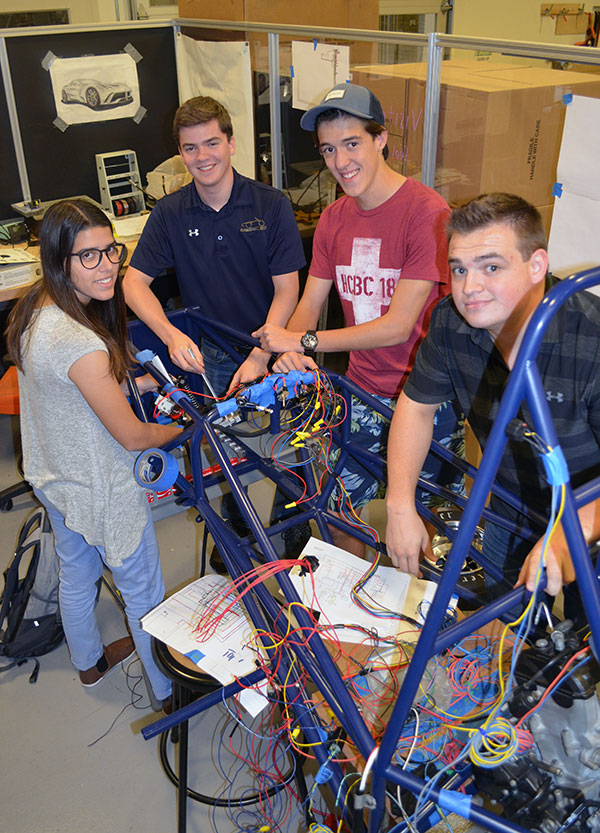

Team president Nick Bilancio (right) with other members of Formula SAE

The Drexel model—all wires and unadorned chassis at this point—is under assembly now in the Innovation Studio. SAE team members work on it through the night, through weekends, and after co-op, casting into form their CAD-designed entry. They are rallied by team president Nick Bilancio, who keeps the high-stakes vibe cranking and aims to have their “DR19” model go up against the best in Lincoln, Nebraska next June.

“While building a racecar is a great challenge, the true purpose of Formula SAE is giving engineers a way to apply what they’re learning in the classroom,” said Bilancio, who is pursuing a BS through the Department of Mechanical Engineering and Mechanics (MEM). “We have to design the whole car in 3D based on 133 pages of rules. It’s something you’re constantly iterating.

“I joined Formula SAE because I wanted to do something cool. But the more I got into it, the more I realized how much I could learn. And anyone can join. Even if you don’t have any experience,” he added. “That is why I am so excited to be the president, to keep this tradition alive at Drexel and hope it gets better every season.”

Last year, the Lincoln Formula SAE contest hosted 1,000 undergraduates and 70 teams. (Another Drexel team is entering a car in the Formula SAE Electric contest for hybrids.)

The competition is not simply about speed, performance, or innovation, said Sean Kennedy, a junior in MEM who serves as the head of manufacturing. Instead, students are judged heavily on their ability to articulate design choices to the automotive industry experts who will grill them.

There are three categories: the dynamic event, which covers how the car performs under race conditions; the design event, in which engineers discuss everything from the shape of the car to its suspension geometry; and the business event, or, how cost-efficient it would be to mass produce their model. Industry experts in the past have come to the competition from Ford, GM, Chrysler, Tesla, and SpaceX, many of them in recruiter mode.

Drexel last entered a car in Formula SAE Lincoln in 2013. However, the car sprung an oil leak and was disqualified.

Bilancio and his team are determined that nothing like that will happen this year. They foresee DR19 taking its rightful place against competitors from Temple, Penn State, Michigan, Florida, among many others.

“Drexel is the engineering and the co-op school,” said Kennedy. “We should be there.”

Employers Love It

Bilancio likes to expound on what Formula SAE can do for a young engineer’s resume. Employers love it, he said, because of the wealth of hands-on design experience engineers gain. Many students even end up certified in computer aided design through licenses gifted to the SAE team by the Massachusetts-based company, SolidWorks.

“That’s a great thing to have on your resume,” said Bilancio. “CAD takes years to master and it’s an essential skill for an engineer.”

Formula SAE students work on the car.

Freshman Josh Deller originally contacted Bilancio back in the summer about joining the team. “I have a background in cars—my dad and I are restoring a 2003 Mustang V6—and automotive engineering specifically is what I want to do when I graduate,” said Deller. “I just love this stuff. I love cars. I love the way we’re looking into how they work. I want to take on as much as I can.”

There is plenty of work to go around. The team has work groups for seven different systems, including chassis, steering, suspension, driver cockpit, wiring/electrical, drivetrain/cooling, and body work. Four potential drivers are training. The car is comprised of 800 parts, some machined at Drexel, others shipped out for work, still others 3D printed – and even that number doesn’t include the multitude of fasteners, lines, and electronics required. And as each new system is completed on its own, it has to be synced with everything else.

“It’s a lot of, ‘Well, that doesn’t work because we changed this, and now the steering isn’t right, but then you gotta change the frame, and, well, that changes the suspension geometry which affects the steering again, but then it doesn’t fit the rules,’ ” said Kennedy, laughing. “We put in a lot of hours.”

Funding for DR19 comes in part from gifts-in-kind, like the CAD licenses from SolidWorks and machining work by Wagner Machine Co. in Illinois. Drexel’s Student Activity Fee Allocation Committee also contributed funds, as well as alumni excited to see the program actively building again.

“But we can always use more funding,” said Bilancio.

The Work That Remains

Much remains to be done. By the end of November, the rolling chassis will be in place. A running car is planned for the end of January. After that, testing to ensure that all systems work together seamlessly will lead up to competition.

“The next two months are critical to us in getting a running car, because we’re planning on rolling chassis—having the car support its own weight—hopefully by Thanksgiving,” said Josh Welsh, a junior in MEM who is heading up the car’s steering design head. After that, it’s just refinements in testing, once we get the driver in the vehicle.”

Nebraska’s course is a flat airfield with cones marking off drive lanes for a tight technical gauntlet. The course itself is designed, said Bilancio, to level the playing field for all entries. That way it’s not merely about money: a team with a larger budget for a faster car can be edged out by a smaller team whose design is more maneuverable.

“It’s not just about who has the best, most expensive motor,” said Kennedy. “It’s a balancing act of weight and power, the suspension and size of the car, the length, the tire size. “

In the end, said Bilancio, “They want us to do more thinking than just, okay, how much power can we give the wheels?

“So, we’ve done that,” he said. “We’ve done a lot of thinking.”