-By Wendy Plump

Throughout her career, Michele Marcolongo has co-founded three start-ups and ushered their products from inception to successful commercialization. Two of them followed a well-trammeled corporate path; the third, generated by a discovery in an academic lab, followed a more bewildering path because there was no playbook for the university innovator.

Throughout her career, Michele Marcolongo has co-founded three start-ups and ushered their products from inception to successful commercialization. Two of them followed a well-trammeled corporate path; the third, generated by a discovery in an academic lab, followed a more bewildering path because there was no playbook for the university innovator.

So Marcolongo, PhD, department head and professor of Materials Science and Engineering at Drexel University, wrote the playbook.

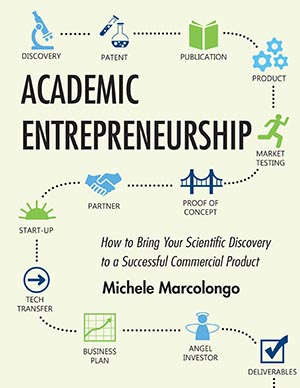

Her book, Academic Entrepreneurship: How to Bring Your Scientific Discovery to a Successful Commercial Product, published in September by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., guides academics along the complex route from lab discovery to commercial viability. While corporate entrepreneurs are common in today’s economy and a vast body of literature feeds their thirst for advice, the academic entrepreneur must negotiate an entirely different set of hurdles.

Marcolongo’s book is “a first step” in addressing those hurdles.

“It’s a movement,” said Marcolongo. “There are an increasing number of academics who are trying to commercialize their research discoveries all across the country. Because, at first, we’re discovery driven rather than product driven, there is a different approach to the early stages of an academic start-up compared to a non-academic one,” said Marcolongo.

“One of the reasons I wrote this book was because colleagues were asking about my experience, ‘What should I put in this operating agreement? Which type of attorney should I use? How should I treat conflict of interest?’ So I thought, maybe I’ll just write it down and they’ll have a baseline for navigating the internal university environment, building business partnerships, and managing student/faculty relationships as well as early stage proof-of-concept and seed funding.”

“One of the reasons I wrote this book was because colleagues were asking about my experience, ‘What should I put in this operating agreement? Which type of attorney should I use? How should I treat conflict of interest?’ So I thought, maybe I’ll just write it down and they’ll have a baseline for navigating the internal university environment, building business partnerships, and managing student/faculty relationships as well as early stage proof-of-concept and seed funding.”

“All that takes time and talent and skills that are different from those of a typical academic.”

Academic Entrepreneurship focuses on the two most common ways to bring research projects to the public: licensing intellectual property through the university to a corporate entity, and forming a new company or startup around the technology. “Licensing is the most straightforward path to commercialization. I totally recommend licensing to an existing company,” Marcolongo said.

However, she acknowledged that while different companies jump into the process at different points, many are unwilling to license intellectual property directly from a university because it is too early in the process. Companies and investors prefer that an idea be “de-risked” by moving it out of research and further into development. The responsibility for that progress falls squarely on the academic. Simply getting an idea to that point can cause many projects to wither on the vine.

In brisk, direct chapters replete with bullet points and sidebars, Marcolongo targets patents and the protection of intellectual property, navigating the technology transfer office, and the research and market analysis phase. “You can’t start without these. You have to see if there’s a market for your discovery. And then you can do everything else,” she said.

She details governmental programs like I-Corps, offered by the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health, that train academics in how to do that search phase and set up the value proposition of a potential business.

The book then moves through the Proof-of-Concept stage, start-up management options, the inclusion (or not) of graduate students and postdocs in the project, incubators and accelerators, the product offering stage, and financing. The book can also be used to train graduate students and post-docs in entrepreneurship.

Finally, Marcolongo includes interviews with other academics and national members of the innovation ecosystem who have forged their own paths from discovery to viability.

Academic innovators need to have creativity, grit and a “measured” level of comfort with risk in order to see a discovery through to viability. Arching over those qualities, she added, is sheer doggedness, the kind that stays with an idea through years of small successes and defeats.

“The thing that we maybe didn’t really appreciate when we first started doing this was how long it takes. These projects can take 10 years to mature. That’s really the average. So, it’s a long commitment,” said Marcolongo.

“The difference for the academic innovator is, the nucleation of the idea comes from research and academic discovery. It has to be shaped from a research idea into a product offering for a market. Mark Zuckerberg wanted to create a way for people to find each other on campus. He had that very clear image already, and then he found a way to make the software do that. But academics may approach a business from the opposite perspective. We might say, we have a software package that can match things and then we have to figure out what to do with it. And that difference means we need more time.

“I think you have to realize you’re running a marathon and not sprinting. But you can stage it and get through it that way. Piecing it out, as I describe in this book, is one strategy.”

Marcolongo’s field of research is biomaterials, or materials that can be implanted into the body to replace diseased or damaged tissues. She co-founded two companies through this research, including Gelifex, which was sold to a major orthopaedics manufacturer; and MimeCore, which commercialized a platform technology of biomimetic proteoglycans. In addition, she co-founded the health IT company Invisalert Solutions. In a past position as Senior Associate Vice Provost for Translational Research at Drexel University, Marcolongo worked to develop strategies to translate research discoveries from the laboratory toward commercialization. She has been with Drexel for 20 years.

Academic Entrepreneurship: How to Bring Your Scientific Discovery to a Successful Commercial Product is available direct from the publisher and through Amazon, where it can be purchased as a conventional book or as an e-book.