When Katy Perry sang “Rise” and “Roar” on the last day of the Democratic National Convention last week [July 28], the country heard her passionate tunes without any transmission glitches. Kudos goes in good measure to four Drexel graduate students.

When Katy Perry sang “Rise” and “Roar” on the last day of the Democratic National Convention last week [July 28], the country heard her passionate tunes without any transmission glitches. Kudos goes in good measure to four Drexel graduate students.

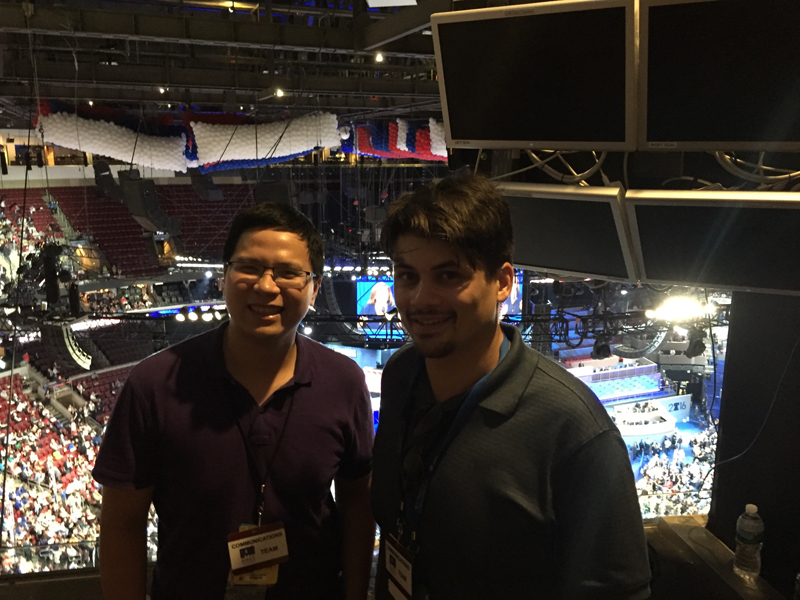

Marko Jacovic ’13, ’15 M.S., Danh Nguyen ’09, ’13 M.S., and Ilhaan Rasheed ’15—all from the College of Engineering’s Wireless Systems Lab—volunteered with the DNC’s communications team. (Mislav Mijatovic, a master’s student at Drexel’s Westphal College of Media Arts & Design, also worked the convention.)

Last Thursday [July 28] afternoon, the students witnessed Perry practice her medley and, perhaps as exciting, made sure her use of a wireless, red-white-and-blue microphone was a success.

Turns out a lot goes on behind the scenes to ensure a challenging event like a political convention comes out sounding loud and clear. The Drexel student volunteers spent five days working six-hour shifts under the auspices of Broad Comm Inc. to ensure broadcasters from around the world could live stream without any issues. (Students from Delaware Technical College also helped out.)

“Every day was high intensity,” said Jacovic, 26, a second-year Ph.D. student in electrical engineering who hails from Penn Valley, Pa.

Wireless devices use radio waves to send communications, such as a video clip of Hillary Clinton’s history-making speech as the first woman nominated for president of a major party. The frequency spectrum is limited, and as a result a massive amount of coordination and enforcement needs to occur to ensure no one steps on each other’s toes—or more accurately on each other’s radio frequency.

If two cameramen, for example, try to use the same frequency, then viewers might see choppy video and sound, static or a lost signal altogether.

If two cameramen, for example, try to use the same frequency, then viewers might see choppy video and sound, static or a lost signal altogether.

“When there’s such a large investment, if broadcasters were to lose quality of service it would be devastating,” Jacovic said.

The broadcasting of a political convention is unlike most other major events. The DNC had about 2,000 registered wireless devices, all vying for a frequency in a tight space where radio waves were bouncing around the arena, said Rich Paleski, director of operations and engineering for WCBS-TV in New York City who helped supervise the students at the event. (He also is a Drexel adjunct professor in Westphal.) In addition, emergency personnel had to have clear communications. It was the perfect storm for a high likelihood of interference.

“This is about as harsh of an environment as it gets for receiving devices,” Paleski said. “It is much more difficult to coordinate than the Super Bowl … or even an inauguration.”

On final analysis, the convention—at least the transmission part—was smooth sailing, he said, and one reason was the work of the Drexel quad. “The students did a great job,” Paleski said. “They understood good radio frequency theory.”

Much of the critical work was clerical. As media entered the convention, the students checked wireless devices against a pre-approved list with the allotted frequencies and tagged them coordinated or not. If a device was “uncoordinated,” then it could not be used to stream content—a situation that arose a few times. The students also worked as enforcers, making sure no one was squatting on someone else’s frequency.

“We traveled the entire area of Wells Fargo,” Jacovic said, “and the adjacent tents. We did the same thing on the floor of the convention.”

“We’re used to sitting in a research lab,” added Rasheed, 25, a native of India who is working on his master’s degree in computer engineering and researching biomedical smart textiles. “We were on our feet the entire time. It’s a tiring job.”

Not that he’s complaining. He and the other students appreciated the unique experience the convention offered.

For Rasheed, the convention foreshadowed the future, he said, where the competition for the frequency spectrum will grow ever more cutthroat as more and more things—the kitchen toaster, that smart fabric track suit, any number of medical devices—tout wireless capabilities.

“We do research in wireless technology,” he said. “The amount of effort it takes to ensure quality was nice to see in person.”

“We do research in wireless technology,” he said. “The amount of effort it takes to ensure quality was nice to see in person.”

Nguyen, 30, originally from Vietnam, said the DNC experience gave him greater motivation for his research.

“The question is whether we can share the frequency band among different broadcasters while still maintaining the quality of service for their programs,” he said.

One such cutting-edge technology is known as cognitive radio, which can survey the environment and figure out which frequency is not in use and latch on to it, explained Jacovic, who, along with Nguyen, conducts research in this area. Another approach is to design reconfigurable antennas that capitalize on the optimal position for the best transmission, Nguyen said.

The convention was not all work. The students found time to celebrity hunt and get some pics. Rasheed’s favorite spotting was “Daily Show” correspondents Jordan Klepper and Hasan Minhaj. Jacovic was excited to catch comedian Stephen Colbert and actress Rasario Dawson. For Nguyen, one highlight was Perry’s practice session.

What about the politicians? The students, ever the professionals, declined to reveal any political persuasions.

“It was more about the opportunity to support such a large and historic event,” Jacovic said. “To be at the center of the event was quite remarkable—and knowing we were able to help it succeed without any major hitches.”