Meet Moncho Alvarado, Author of “Greyhound Americans”

by Liz Waldie

May 5, 2023

For Moncho Alvarado, a Cihuayollotl trans Xicanx poet, it was her family’s stories that kickstarted her journey as a writer. Much of her family hails from Mexico, and as undocumented immigrants early on, they looked to each other for support. Once a week or so, they got together to tell the stories of their past. Alvarado remembers being in awe of their stories and everything they’d gone through. She sat there glued in her spot, listening to them as they unraveled their history before her.

For Moncho Alvarado, a Cihuayollotl trans Xicanx poet, it was her family’s stories that kickstarted her journey as a writer. Much of her family hails from Mexico, and as undocumented immigrants early on, they looked to each other for support. Once a week or so, they got together to tell the stories of their past. Alvarado remembers being in awe of their stories and everything they’d gone through. She sat there glued in her spot, listening to them as they unraveled their history before her.

“I fell in love with that type of oral storytelling and from there fell in love with reading and written word,” Alvarado explained. “I would just walk to the library and anything I could absorb, I really loved. It was like a seed that was sowed when I was younger.”

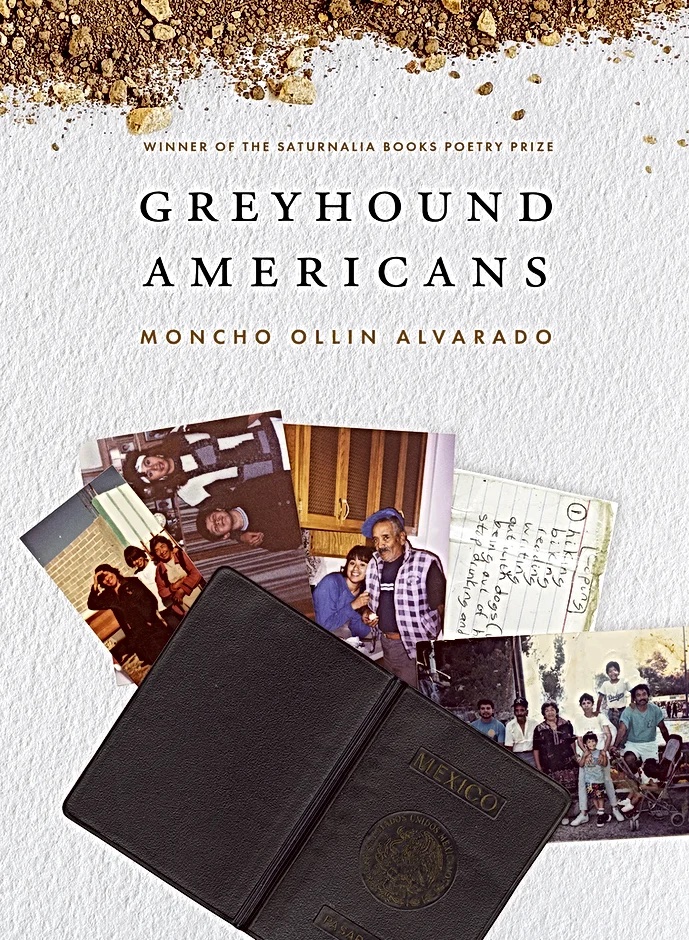

Now, Alvarado’s work has appeared in numerous publications and at museums, and her debut poetry collection, “Greyhound Americans,” was the recipient of the 2020 Saturnalia Book Prize, selected by Diane Seuss.

Alvarado will join us for a poetry reading at the Drexel Writing Festival on Monday, May 8 from 12–12:50 p.m. in the Stern Room on the third floor of Hagerty Library. Learn more about Alvarado in the Q&A below, and view all Drexel Writing Festival events here.

Can you describe your journey from writing for yourself to putting your work out into the world?

It was a long time, because of my upbringing and my past. I had to work full time and go to school full time, and sometimes I had to work more and go to school part time. It took a while for me to figure out what I wanted to do, and there weren’t that many opportunities for me starting out. But eventually I got to the point where I was able to transfer from a community college to a four-year college, and I really started getting more into my craft. I started taking creative writing classes, which helped me hone my craft and meet other authors. Once I saw queer folks of color that were doing it, I was like, “Oh, they're like me, and I can do it.”

Where do you find inspiration?

For me inspiration comes from the same folks that I grew up with—friends, family members—still doing what they do. Still hustling, still struggling. It comes from my community back home, and from the trans and queer communities. For a while I wasn't writing, because I was going through depression. But I was regularly listening to a podcast called “TransLash,” and they were talking about anti-trans films. The more I started getting into it, the more I started getting outraged and angry. There's a sense of fire that never went out of me from when I was younger. That teenage fire that was just sick of this system. There are over 500 anti-trans bills that are trying to be passed in the United States, and I started thinking about what type of poetic form I would like to use to erase the hate that's in there and bring out the love and life that we as trans folks have. So I started creating poems from there.

What place does visual art hold in your creative practice?

Over the years I’ve dabbled in photography, collage and other mediums that I connect to, but mostly it's just for myself. What I usually do is create collage pieces using nature and documentation from my grandparents—and from myself—to elicit naturalization, what does naturalization mean? Questioning whose authority is given to naturalization, especially as indigenous folks from Mexico. It gives me another lens to figure out what I want to do visually. How can I do this in a poetic sense?

For example, in “Amá Teaches Me How to Whistle,” I was thinking, “How can a poet mimic the physicality of sound on the page?” There was once a class I was taking, and they would ask if there was a certain symbol that we could try to mouth that does not sound like “i” or “e,” like an exclamation mark. That stuck with me a lot. When I was researching the history of the asterisk, I really gravitated towards that because it reminded me of the sun. It also reminded me of lips. It also reminded me of whistling. It reminded me of my mom teaching me to whistle, and I thought I could use that symbol on the page and try to see if people would mouth it.

What is the most rewarding part of teaching and guest-reading?

Just being in community. I think that's what I started learning early on in poetry, since it's such a small group. Even remembering open mic nights in high school and going to different places as I grew up, it was always a sense of community. I try to push myself to build that, because I'm in love with poetry and it feeds me. I remember doing a reading once, and just being there for the people that were asking questions afterwards, I was like, “I will give you as much as I have.” It’s about understanding that poetry is outside of your bedroom or outside of the bathroom or outside of any other space—it's out there. It takes courage to be out there and try to be part of community, but it's always there virtually, and physically as well.

What is the value of learning from other authors and artists?

For me it's seeing what they're doing differently on the page, and hearing what they're doing differently. I think everyone has something to teach. And everyone has a sense of self that is specific to them and sacred to them, and I wouldn't understand or know how to write their type of poetry. What I get from it the most is a sense of what I would do compared to their work. Like, how would you write a breakup poem? I'm going to put everything in the kitchen sink into it, whereas another person’s might be finished with red angriness. So it's a sense of connection and exchanging different creative ideas.

As a trans poet of color, how do you navigate the landscape of people whose views oppose yours?

I think the hardest thing for me as far as I've gone through my journey is understanding if other people are willing to hear, understand and maybe change. I'm willing to listen to you, but if you're not willing to listen to me, I can't do that. I think that's the most important thing: don't sacrifice yourself and don't put yourself through that emotional, mental and spiritual labor. There are folks that are just like, “I don't get it, but I respect you,” and that's a start, because at least there's mutual understanding and respect. If you're queer or trans, first and foremost, just take care of yourself.

Do you have advice for students who might be in a similar situation as you?

Understand that you're not alone, there's always an afterwards, there's always healing and there's always people there that are willing to help you, as long as you try to connect with them. We do, unfortunately, live in a world that is run by a lot of individuals who really don't care about people’s feelings. But you should take care of yourself and your people that you love and care for, and the community that raised you or the community that you built. And if you're not ready to come out, don't do that just because you're peer pressured by social media or other people. Take your time. Look at me—I took my time because of how much my body and mind needed that time to heal and process it, and then I finally opened up.