The Future Ghost Forests of New Jersey

By LeeAnn Haaf

June 13, 2022

Studying the impact of climate change and sea-level rise

In the Delaware Estuary region, trees close to salt marshes are at risk of death as seas rise and coastal flooding pushes farther into low-lying forests. LeeAnn Haaf, a PhD candidate in Drexel University’s Biodiversity, Earth and Environmental Science (BEES) Department, studies the effects of climate change and sea-level rise on low-lying tree growth in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States. She is also a wetlands coordinator with the Partnership for the Delaware Estuary.

This article originally appeared in Estuary News and was written by LeeAnn Haaf. It was featured by The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University on May 17, 2022, and is re-published with permission.

Researching the Effects of Coastal Flooding on Loblolly Pines at Jakes Landing, New Jersey

Jakes Landing is a centuries-old access point to Dennis Creek in Cape May, New Jersey, where the forest landscape abruptly drops into a tidal saltwater marsh. Close to the marsh, row after row of dead Atlantic white cedars jut out of the ground like spikes. Just beyond those are swaths of statuesque loblolly pines.

The forest is healthy now, but these trees are in danger. Most trees in the Delaware Estuary region that stand close to salt marshes are at risk of death due to sea-level rise.

Ghost Forests

Sea-level rise and climate change are pushing coastal flooding farther into low-lying forests and slowly killing nearby trees, causing what often are called ghost forests. Eventually, the swaths of healthy loblolly pines will become inundated with water from flooded marshes and likely suffer the same fate as their neighbors, the Atlantic cedars.

However, careful research and studies of trees while they’re still healthy can help managers understand how frequent salt marsh flooding might affect them before they die and where to focus their efforts to prevent more trees from dying.

Loblolly pine itself is not an imperiled species. It’s one of the more abundant pines in the eastern U.S. (mainly towards the South). Over the last 100 years, loblollies at Jakes Landing have grown under various conditions — droughts, blizzards, heat waves, hurricanes and coastal floods. Under these stressful conditions, the pines didn’t grow as much as they might under gentler ones.

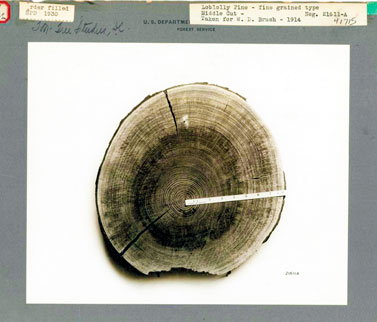

As trees grow new wood each year, patterns about their health and conditions emerge within the trees’ rings. With sea levels rising, increased flood frequency in the forests might result in thinner and thinner rings, which could foreshadow tree death.

Reading the Rings

By collecting tree ring samples, researchers uncover how weather, saltwater and climate are affecting trees that are exceptionally close to marshes at Dennis Creek. Wetlands researchers from Partnership for the Delaware Estuary (PDE) have carefully removed about 50 tree core samples from the pines at Jakes Landing to observe patterns in annual tree growth.

The core samples are about the size and shape of a narrow drinking straw. Extracting them doesn’t harm the trees, but the cores help researchers study patterns in tree growth relative to climate and tidal water levels changes over time.

After sanding, measuring and analyzing core samples, PDE researchers found that loblolly pines at Jakes Landing grew best during warm winters but often grew less when tidal water levels in the previous autumn were high. New Jersey is the farthest north in the United States where loblolly pine grows.

Winters in the Delaware Estuary region are chillier than loblollies prefer, but over the past years, winters in the Delaware Estuary have gotten warmer due to climate change. Increased salt marsh flooding, however, could counteract the benefit of warmer mid-Atlantic winters and threaten the health of low-lying loblolly pines.

PDE’s research will help foresters and land managers anticipate how well these trees will grow in the future in different areas experiencing increased flooding. And perhaps their findings will provide details that help factor climate change and sea level rise into research management plans.