Environmental Science PhD Student Lena Champlin Publishes Children’s Book on Climate Change

By Gina Myers

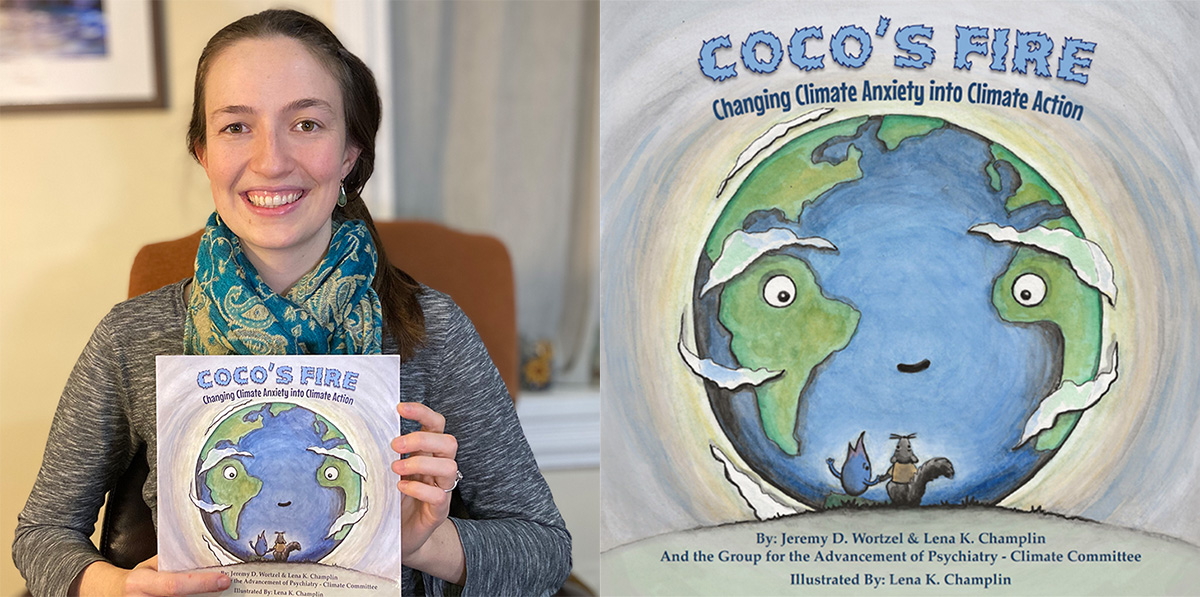

Lena Champlin, an environmental sciences doctoral student, co-wrote and illustrated the children's book Coco's Fire: Changing Climate Anxiety to Climate Action, which was recently published.

Lena Champlin, an environmental sciences doctoral student, co-wrote and illustrated the children's book Coco's Fire: Changing Climate Anxiety to Climate Action, which was recently published.

January 10, 2022

The idea began with Lena Champlin’s community outreach work at the Academy of Natural Sciences. One day, she asked a young girl what she knew about climate change. The child’s caretaker jumped in to say, “Oh no—we don’t talk about climate change.”

This led the fourth-year environmental science doctoral student to consider the questions: At what age do we begin talking to children about climate change? How can we talk about climate change in an accessible way for children? And how can we talk about it in a way that is inspiring, rather than upsetting?

It is a conversation that she began having with her partner Jeremy Wortzel, a medical student at the University of Pennsylvania who is pursuing child psychiatry and is interested in how the environment impacts mental health. Due to their shared interest in climate anxiety, the two decided to partner with the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry’s Climate Committee and collaborate on a children’s book. The result, Coco’s Fire: Changing Climate Anxiety into Climate Action, was recently published.

“Climate change is something that’s scary for parents and scary for me as well. I think that fear can lead us to not want to introduce this topic to kids, but I think these discussions can be an important collaborative learning process between parents and their children,” says Champlin.

“That collaboration is really empowering. You can work with your child to join these conversations and learn together. Additionally, you are joining work that’s already happening by scientists, activists and policymakers that really care about climate change. You and your child are joining a community, and I think that can provide a lot of hope.”

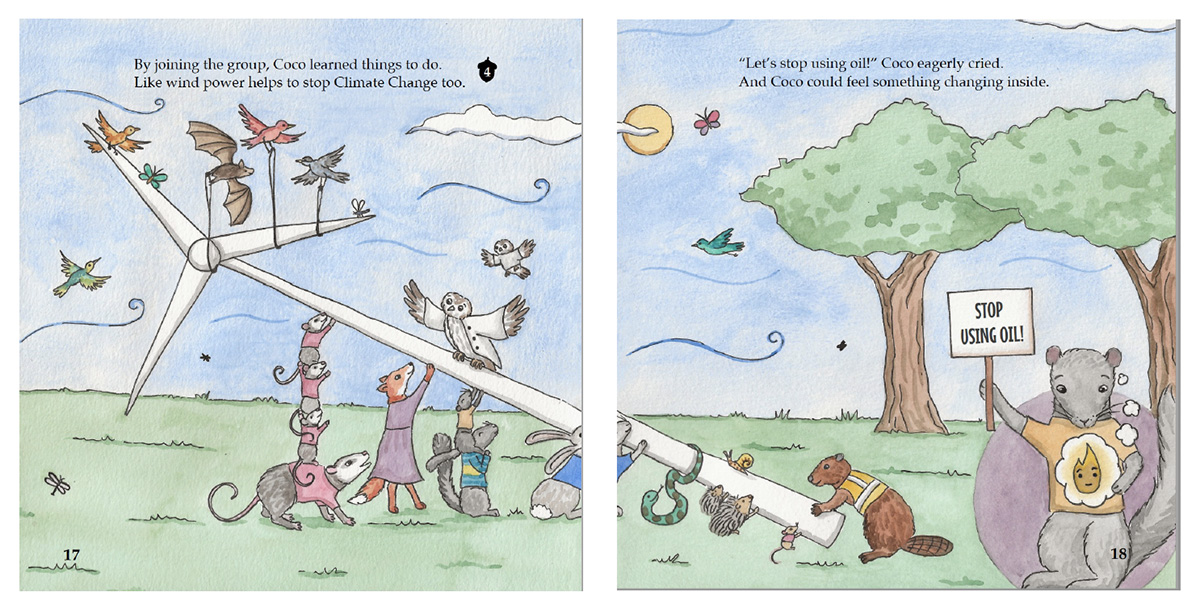

An interior spread from Coco's Fire: Changing Climate Anxiety into Climate Action

An interior spread from Coco's Fire: Changing Climate Anxiety into Climate Action

The book is geared toward early elementary school students and follows Coco the squirrel and her dad on their quest to stop climate change. Over the course of the story, the things that worry Coco wind up inspiring her into action. According to the book’s description, “The book offers a model conversation written by mental health professionals and environmental scientists for how to have ‘The Climate Talk’ with children.”

For adults who are concerned that their children are too young to be exposed to the topic of climate change, Champlin points to a recent article from Yale Climate Connections. “It describes that we should always talk about the environment because introducing things at a younger age increases people’s resilience to build on those concepts,” she explains. “So starting to talk about climate change at a young age is valuable because it gives kids resources to build upon over time. How we talk about climate change should depend on a child’s age, but this early communication is key to understanding the issue deeply.”

Champlin and Wortzel wrote the book together in collaboration with the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry - Climate Committee, and Champlin served as the illustrator. Throughout the book’s development, they met with the committee to make sure their message was psychologically age appropriate and communicated in a way that would be hopeful. This approach to communication also applied to the illustrations.

“There’s so much visual representation of climate change that is terrifying, such as wildfires and polar bears standing on little ice caps,” explains Champlin. “Imagery is incredibly important to how we respond emotionally to things.”

Champlin hopes that their book offers a different view than a lot of other children’s books on environmental science. “I think historically the message a lot of kids get from books like The Lorax is that adults messed up the Earth and it’s on them to fix it, which isn’t very empowering and can be overwhelming,” she explains. The message she wants readers to take away from their book is simple: “You are not alone—you can join with the local and global communities of scientists and activists already working to address climate change. Your contribution is important and powerful.”

Since the book’s release, the response has been positive. The authors have been receiving emails from parents and teachers, and they have received pictures of children reading and enjoying the book.

Writing the book has been a dream come true for Champlin, who always wanted to be a children’s book author. It lets her bring her love of science and art together, and she knows the education they provide.

“There is a lot of nonformal education of environmental science in different spaces like museums, nature centers, and children’s books. I think these spaces are critical in how children perceive their contribution to environmental science, and children’s books specifically provide a foundation for how children relate to challenging topics like climate change.”