Rivers in History Course Brings the Past into the Future with ArcGIS

By Breath-Alicen Hand ’21

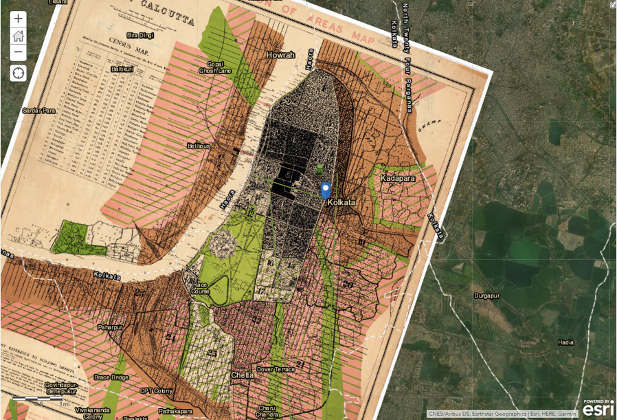

EPRichards 1917 Overlayed on 2016 Population Density

EPRichards 1917 Overlayed on 2016 Population Density

April 19, 2021

Associate Professor of History Debjani Bhattacharyya, PhD, has overcome the challenges of social distancing in her usually hands-on course Rivers in History, using ingenuity and advanced technology. In ordinary times, Bhattacharyya’s students would have enjoyed the benefits of fieldwork in the Delaware River watershed through landscape exercises at one of Philadelphia’s many parks, trails or gardens. In the times of COVID-19, this simply was not an option.

This term, instead, Bhattacharyya teamed up with Steven Melly of the Drexel Urban Health Collaborative to develop an “ersatz deep-learning experience” which provided students with the opportunity to learn and use ArcGIS, a geographic information system. ArcGIS is a powerful tool for performing analytics using geographic information and maps. Access to ArcGIS usually means paying an annual subscription fee, but thanks to Drexel’s Educational Site License, the training and the software came at no extra cost to students. This technology can be used in virtually any field, and its mastery has tangible value beyond the academic world.

The results are, in the words of Bhattacharyya, “visually sophisticated” story maps that guide viewers through three kinds of river-city relations along India’s coast: Buckingham Canal in Chennai, Hooghly River in colonial Calcutta, and the water bodies and swamps of contemporary Kolkata. For Environmental Policy graduate student Hayden Smith ’21, this course cemented prior inklings about the “value of using ArcGIS and story maps for historical research.” He is convinced enough that he now incorporates this technology into his professional work. Part of the success of the course seems to be that, as Smith observed, “across the course, material was highly contextualized.”

Before undertaking the ArcGIS projects, students were challenged to consider the perspective of landscape architect Dilip da Cunha. He argues that rivers, as people typically view and experience them, are not a natural phenomenon but are products of human effort and their desire to exert control over natural systems. He challenges others to imagine them not flowing within straight lines, but as “open fields of wetness.” This is not mere provocation, but a useful prompt for understanding and engaging with rivers differently.

Hooghly River, Calcutta

Hooghly River, Calcutta

To that point, throughout the course, students were asked to consider two fundamental questions: First, can the histories of rivers help us understand how human design acted upon and transformed rivers and watersheds? Second, how can the attention to materiality of the river help us transform our understandings of our environment and offer new methods of doing environmental history?

“Rivers are living beings, beings which move, change course, give life and also die,” says Bhattacharyya.

Understanding rivers differently not only has implications for students’ coursework but also relates to local and global political and power relations. For millennia, those who have “controlled” rivers often controlled their symbolic value in addition to their uses for navigation, energy and potable water. To gain a sense of this perspective to apply to their target rivers/cities, students also examined the nature/human histories of various other rivers including the Mississippi, Atchafalaya, Ganges and Rhine.

In application, one student group investigated the cultural and historical meanings of waterbodies in Calcutta, as well as the river’s influence on the city’s growth over time, including the growth of infrastructure. Flipping that on its head, two other student groups investigated how urbanization has transformed watersheds over time, providing an understanding of how rivers in individual cities have reached their current states. For Smith, this course enabled a deeper understanding of the relationship between rivers and humans over time. This is not simply an academic exercise. For practitioners of all kinds, these historical perspectives could offer insight into how to work with watersheds, rather than against them.

The history of rivers and humans provides insight into the present and into how coastal cities might face the challenges of climate change.

Like many coastal cities, both Chennai and Kolkata/Calcutta are grappling with the impacts of a warming globe. More frequent, higher flooding and more large and powerful storm systems are pushing activists to demand protection from the adverse effects of climate change while forcing decision makers to design and implement programs and policies with climate change adaptation and mitigation in mind.

Undergraduate history student Anna Shetler ’21 explains, “Not only can ArcGIS be used for history classes, it can be used to map out environmental areas of concern, illustrate the need for action, plot the history of a region in a time lapse fashion and countless other uses.”

ArcGIS is a versatile tool with the potential to assist and influence decision makers in their efforts to shape resilient cities along with an abundance of other applications. These Drexel students now have valuable experience in using this powerful tool thanks to the collaboration and innovation of Bhattacharyya and Melly through a course that was, in the words of Shetler, “easily one of the most engaging and interesting courses I have had the privilege of taking.”

If you’re looking for a course that offers an accessible way to explore ArcGIS, the Rivers in History course makes that possible while also offering a multi-layered view, through historic and contemporary mapping materials, into the history of human/water system interrelationships.