Frame of Mind

By Kylie Gray

January 15, 2018

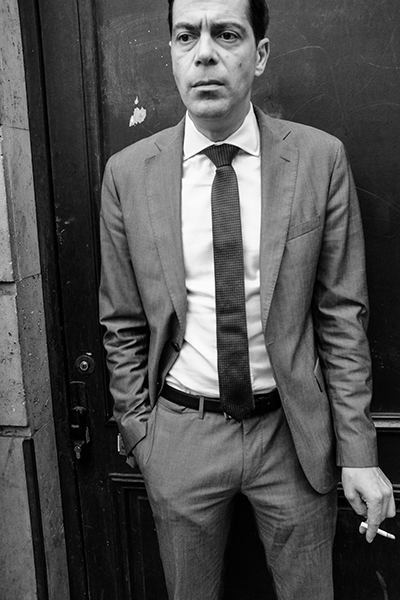

Smoker, Paris, France

Smoker, Paris, France

Street photographer and Drexel anthropologist Brent Luvaas, PhD, has a way of blending in as he walks city streets. If he’s lucky, a certain slant of light will catch his eye and he will set the exposure for maximum depth of field, waiting patiently for the right subject to walk in front of the lens. Most often, however, the typical elements of a photographer’s labor — setup, composition and lighting — happen almost instantaneously.

For Luvaas, there is a kind of mindfulness implicit in the craft.

“The more I do street photography, the more I see it as a life practice rather than a visual practice. It’s about being in the world more fully,” he says.

Followers of his Instagram account @streetanthropology know that Luvaas has a talent for capturing the rich diversity and subtle interactions of people in urban spaces. The subjects he photographs — the complexity of their expressions — suggest solitude, throwing light onto the internal worlds we often inhabit.

Luvaas first made a name for himself in the photography world as the street-style blogger behind Urban Fieldnotes and later as author of the book “Street Style: An Ethnography of Fashion Blogging.”

He adheres to an approach known as “autoethnography”: In order to understand the perspectives of street-style photographers, he became one.

Brent Luvaas, PhD

Brent Luvaas, PhD

Luvaas was drawn to fashion as the domain of outsiders — creative people who felt disenfranchised, even alien. Street-style fashion bloggers widened the conversation; suddenly, he says, kids in Cape Town and people of all body types were having an impact on mainstream fashion.

Embracing this “radical inclusivity,” Luvaas built his Urban Fieldnotes blog as a space to document his street-style photography from around the world. In between teaching classes at Drexel and publishing in scholarly journals, he jostled with photographers at Jakarta, Singapore and New York Fashion Weeks, and shot photo collections for BET and Refinery29.

Urban Fieldnotes had amassed press and thousands of followers by February of 2016, when Luvaas decided to walk away from the project of five years, overwhelmed by the reductive perspective he found himself directing at others and even himself.

“If you are training yourself to recognize coolness from the perspective of the fashion industry, it means that you’re going through this massive checklist when you’re walking down the street, and you’re crossing most people off,” he says.

The disparate yet interwoven elements and coincidences that happen within an urban space drew Luvaas to a broader form of street photography, without the focus on street fashion.

His @streetanthropology posts are influenced by the classic street photography of Paris in the ’30s and ’40s, he says, and the grittiness and heavy shadows characteristic of New York street photography in the ’60s and ’70s. While his work is not always completely candid, his portraiture has become a means of getting to know local fixtures.

“Street photography has always been a practice of wandering aimlessly,” he says. “It’s a reimagining of what it means to move through the city. You engage with different people than you would ordinarily.”

It is a practice of detail, nuance and sometimes humor. Luvaas’ photos illustrate the “accidental harmony that happens within an urban space” as strangers are brought together for a moment in time.

“It’s not about looking at the ‘other’ from a distance,” he says. “Street photography forces you to deal with environments from within. It’s a position of involvement.”